Creatine started turning heads in the athletic world during the early 1990s, long before I ever stepped foot in a gym. Its promise to help boost power output gripped so many athletes, but as time rolled on, folks noticed limits with standard creatine monohydrate. The search for something better, smoother on the stomach, and possibly more absorbable, led to a wave of new creatine salts and chelates. Di-Creatine Malate, a compound joining two molecules of creatine with malic acid, wasn’t born out of luck or marketing—it grew out of a need for a product that some say goes easier on the digestive system and supports energy at the biochemical level. Looking at those early supplement days, people weren’t satisfied just swallowing scoops of white powder. They craved performance minus the bloat and grit, and chemists responded by tethering creatine to other molecules, hoping for a smarter, friendlier supplement.

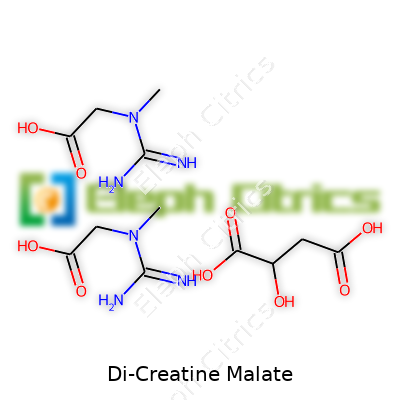

Di-Creatine Malate stands apart from the typical jug of plain creatine that most gym lockers used to hide. The main idea involves pairing two units of creatine with one of malic acid. Creatine, by itself, supports quick energy through ATP recycling. Malic acid, central in the Krebs cycle, pulls from a different kind of energy pathway every runner, lifter, or everyday mover depends on. The two together give athletes and regular people a compound touted to dissolve better, cause less bloating, and provide a dual boost through different metabolic avenues. Seeing this on a shelf, I see more than a label—I see a snapshot of how sports nutrition keeps evolving, always chasing a better edge or at least a smoother mixing cup.

Most folks, myself included, notice quickly that Di-Creatine Malate doesn’t clump like old-fashioned powder. The malate component lends a slight sour taste, a nod to its fruit origins, and easier mixing with water. The compound appears as a fine white to off-white powder, freely soluble in cold liquids. The molecular formula speaks to the binding: two creatine molecules locked to malic acid (C10H16N6O5). It’s less hygroscopic than regular creatine monohydrate, so open tubs stay usable longer without caking. I’ve watched supplement brands tout this improved texture, but from the user’s side, the big win most days comes in the glass—less grit, less residue, and for some, fewer digestive complaints.

Regulations for labeling supplements can turn into a maze, but serious brands spell out the source and ratios of their creatine sources. On a Di-Creatine Malate label, I expect to see the total weight per serving, breakdown of pure creatine content (which isn’t ever 100% due to the malate component), and the form used—no one benefits from hidden blends. Authentic providers offer certificates of analysis, detailing purity thresholds often above 99%, and include heavy metal, microbial, and solvent testing results. I’ve found consumers trust clear, batch-specific documentation, and every time a company comes forward with test results, the whole industry takes a step toward better safety. Claims on labels should reflect actual science, not marketing fluff, and I routinely remind fellow athletes to check if their tub contains just Di-Creatine Malate or some watered-down mix.

Production steps for Di-Creatine Malate reflect blending chemistry with quality control. Getting a stable bond between two creatine molecules and malic acid happens through a controlled reaction—a process that avoids high heat and excess moisture to keep the finished product potent and clean. Chemists dissolve creatine in water, add malic acid, and carefully neutralize, keeping specific pH and temperature ranges to promote correct linkage. The product gets filtered, dried, and milled into a consistent powder. Every batch passes through screens to ensure particle size stays consistent—this step can make all the difference in mixability at home. In the world of supplements, these seemingly simple tweaks in production get magnified in user satisfaction or disappointment.

The link between creatine and malic acid forms a salt—these bonds help hide some of creatine’s taste and improve blending with water. There’s no irreversible chemical change; the body separates the compound back into creatine and malic acid during digestion. This bond changes creatine’s physical properties but keeps its biological action. Manufacturers don’t change the base molecules—no one’s adding dangerous modifications or weird substituents. Instead, the focus stays on making creatine easier to store, blend, and swallow. I’ve tested some of these in my own kitchen, dissolving various forms, and Di-Creatine Malate stands out for leaving fewer gritty bits behind. The industry keeps experimenting, but simple chemical pairing still beats complex synthetic derivatives for safety.

Supplements rarely travel under a single name for long. Di-Creatine Malate sometimes appears as Dicreatine Malate, Creatine Dimalate, or just “malic-acid bonded creatine” on labels. Some brands print proprietary names or trademarks, adding more confusion, but substance counts more than branding. If I glance through market offerings, I spot various powders and capsules, all referencing the bonded nature of these two molecules. Quality indicators don’t rest in catchy names but in accurate purity and creatine content reporting. Clear labeling, using recognized synonyms and avoiding misleading blends, helps customers make choices rooted in information, not impulse buying.

Safe production rests on three pillars: raw material quality, clean facilities, and consistent processing. Any supplement, and especially something used daily like creatine, demands strict GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices). Facilities need to prevent cross-contamination and verify every batch with third-party testing. Most brands investing in high-grade Di-Creatine Malate follow ISO and HACCP protocols to cover both safety and traceability. Responsible operators never cut corners: they source pharmaceutical or food-grade malic acid, test for heavy metals, and publish transparent certificates. If one product leaves out batch certification or clear contact information, that’s usually my cue to avoid it.

Sports nutrition leads the charge for Di-Creatine Malate. Strength athletes, sprinters, and even endurance competitors grab for it hoping for rapid ATP recovery and improved performance. Its popularity also stems from claims of gentler digestion and better solubility—qualities that matter if you’ve ever tried to down a chunky, chalky supplement before a heavy workout. Some supplement stacks incorporate malic acid’s potential to support energy metabolism, so cyclists and high-intensity trainers often include this compound in their routines. Outside sports, there’s emerging interest in neurological and recovery research, given creatine’s effects on cognition and ATP in brain and muscle fatigue. This application isn’t hype—studies point toward real potential, and the field keeps growing.

The research journey trails the supplement’s popularity. Peer-reviewed studies focus on bioavailability—does Di-Creatine Malate really absorb better or hit peak muscle creatine faster than monohydrate? Results stay mixed; some users claim less water retention or bloating, but group studies don’t always replicate those outcomes. The malic acid component brings its own research trail, mostly in the context of the Krebs cycle and possibly less fatigue, but definitive answers for athletes remain sparse. Brands invest in ongoing lab tests: solubility, stability over time, and performance outcomes in real-world activity. Serious innovation also tracks impurities, to make sure the final product won’t hurt health. As research grows, scientists look beyond simple performance markers, examining links to cellular recovery and neurological benefits. The open questions keep researchers busy and users curious for new results.

Safety reviews paint creatine, and by extension Di-Creatine Malate, in a positive light when taken as directed. Reports of adverse effects like stomach upset or muscle cramping mainly track poor hydration or overuse, not ingredient toxicity. Studies running for months in healthy adults rarely uncover kidney or liver risks at standard supplement dosages. The addition of malic acid, naturally present in many foods, doesn’t add measurable toxicity risk. Regulatory authorities and scientific panels back safe use, yet encourage ongoing monitoring for outliers and long-term scenarios in special populations. Every new lot goes through routine heavy metal scans, microbiological testing, and solvent checks. If something fails—users deserve alerts and recalls, not cover-ups. With so many people adding supplements to daily routines, safety vigilance never gets a day off.

Future directions for Di-Creatine Malate and similar compounds lie at the intersection of supplement transparency and deeper efficacy studies. Supplement companies have a chance to nurture trust by opening up full ingredient sourcing, third-party batch verification, and more head-to-head comparisons with both monohydrate and other creatine salts. Scientists continue drilling into the subtle differences—looking for variations in energy, muscle retention, and cognitive support between creatine types. Innovations in delivery, such as better dissolution granules or drinkable, stable forms, might help more everyday folks use these benefits beyond the weight room. Simpler packaging backed by genuine science and robust testing will help this supplement carve a long-term spot in sports, wellness, and clinical recovery. The dialog between users, brands, and the research world will drive the next evolution, favoring those who invest in both safety and clear communication.

Creatine keeps showing up among athletes and gym-goers, but not every creatine supplement works the same. Some people pick up regular monohydrate and stick with it, but Di-Creatine Malate brings a fresh angle by combining creatine with malic acid. That extra ingredient isn’t just a fancy add-on. My own experience using both forms made it pretty clear: workouts start to feel different in a real way.

Monohydrate fans know about the water weight. That’s just part of the ride, but Di-Creatine Malate creates less of that puffy feeling. This has something to do with how malic acid, found in many fruits, helps the body turn food into energy and makes creatine easier on the stomach. Fewer complaints about cramping or digestive problems. People cutting for sports find this makes sticking to supplement routines a bit easier.

The whole point of creatine rests on its power to restore adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the quick energy currency inside muscles. Adding malic acid to the mix seems to boost the body’s ability to keep those energy cycles running. Studies show creatine in almost any form helps with repeated sprints, heavy lifts or push-to-failure workouts. Di-Creatine Malate claims to sharpen this effect by helping power flow in muscle cells.

Lifting at the gym tends to feel more explosive—my bench reps didn’t just look good on paper, they felt easier set to set. That’s not about hype. Research from the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition backs up improved power output and endurance for folks supplementing with this blend.

Mixability sounds like a small matter, but no one wants grit or muddy water swishing around in a shaker bottle. Di-Creatine Malate dissolves better, stays clear and neutral in taste, and works in almost anything you drink, morning or night. Choosing a supplement is easier when it doesn’t turn every glass into a chore.

Many athletes ask about stomach upsets, dosage, and absorption. Di-Creatine Malate often slides into routines at 3 to 5 grams per day and skips the bloated belly. The improved solubility comes from the malic acid, since it helps creatine slip through the digestive tract and reach muscle tissue. Some lifters in my circle found they didn’t have to back off dosage or cycle off as often because their bodies tolerated it better.

People often look for the cheapest tub, but quality and effectiveness matter more than saving a few dollars. Third-party testing, clear ingredient lists, and picking brands with strong reviews matter just as much as which type of creatine lands in your cart. Checking for certifications—like NSF Certified for Sport or Informed-Sport—works as another way to dodge impurities or dodgy manufacturing.

Supplements only show results when combined with proper hydration, recovery, and nutrition. Di-Creatine Malate won’t turn a lazy routine into a champion’s performance, but for athletes looking to push reps, recover faster, and train more days per week, it brings a real boost. The lower rate of bloating and improved absorption let people stick with it longer.

Di-Creatine Malate marks another option for strength-focused folks, runners, and busy athletes hunting for an edge without digestive drama. It works best with a smart diet, steady sleep schedule, and the discipline to listen to your own body’s response.

Anyone who spends time in the gym sooner or later bumps into creatine. Most supplement shelves carry tubs labeled “Creatine Monohydrate” in bold print. Then you spot “Di-Creatine Malate” and wonder if some secret formula is hiding behind a fancier name. I remember that confusion, too. Shopping for better results, nobody wants to pay extra just for fancy buzzwords. It helps to know what’s actually in the scoop.

Creatine monohydrate looks like a fine white powder and has been tested for decades. It’s safe, reliable, and cheap. The body naturally turns it into energy for lifting weights or running sprints. Di-creatine malate has an extra piece—malic acid. Supplement makers connect two creatine molecules to one malic acid molecule and say this combo helps your body use energy better and helps you feel less muscle fatigue during tough workouts.

Years ago, I tried switching from monohydrate to malate after reading user reviews. I noticed the malate version mixed more easily in water and my stomach felt less upset. The reason seems simple: malic acid dissolves well and may help digestion. Some friends told me they felt less bloated with malate, especially compared to days when big spoonfuls of monohydrate left them feeling heavy before a workout.

The malic acid part has its own story. Malate pops up in the citric acid cycle, the body’s way of turning food into energy. Some small studies hint that di-creatine malate could support those intense bursts of movement—like sprinting—since malic acid plays a role in that cycle. Still, research on this is pretty thin compared to the mounds of evidence backing monohydrate for building strength, muscle, and power.

Anyone who’s tried mixing regular creatine in cold water has probably seen clumps floating or grit settling at the bottom. Di-creatine malate breaks up easily; I noticed no chalky aftertaste. Taste and texture matter if you’re drinking this every morning. Malate sometimes leaves a slight tart finish. Some people like it, some find it distracting.

Price does set these apart. Monohydrate powder is usually much cheaper, and research proves it builds muscle and supports athletic performance. Di-creatine malate, with its extra acid, often costs more per serving. The decision comes down to whether the small potential difference in muscle soreness or digestion is worth paying double or more.

My experience tells me most lifters get the results they want from regular monohydrate. For those with stomach trouble, or if bloat is stopping you from finishing reps, then di-creatine malate is worth a shot. Safety is on your side for both—neither is risky for healthy adults when following recommended doses. Independent lab tests show monohydrate continues to pass purity tests around the world.

If anyone asks me, I tell them to try both and see what makes their workouts better. Records and real-world results both point to monohydrate as the most cost-effective choice. For athletes who like to experiment, malate versions add a twist that may suit their routine, especially when digestion becomes an issue during a tough training cycle.

Sports nutrition stays full of promises. Claims explode faster than evidence piles up. Until more researchers spend time testing di-creatine malate on larger groups and over longer periods, creatine monohydrate remains the old reliable. Lifting is about moving steadily forward—every athlete deserves options, but also clear, honest truths about what’s in their shaker cup.

Looking at Di-Creatine Malate, this supplement shows up as an alternative to regular creatine monohydrate, a favorite among athletes and gym-goers. People sometimes choose this version because of its supposed improved solubility and reduced water retention. In the world of supplements, Di-Creatine Malate brings together creatine and malic acid, both of which play roles in supporting energy during intense physical activity.

From years spent in gyms and lots of experimenting, I’ve found that 3 to 6 grams per day remains the sweet spot for Di-Creatine Malate, lining up with what supplement companies suggest. Most products label their serving sizes between these numbers for a reason. Clinical data on this exact form isn’t as plentiful as on creatine monohydrate, but experts often lean on similar dosing because one molecule of Di-Creatine Malate provides almost the same amount of usable creatine.

Competitive athletes I know usually stick to around 5 grams daily, taking it with a meal. For beginners, starting at 3 grams and then moving upward as their body adapts makes sense. Splitting the dose—half before and half after training—can help with workouts and recovery.

Di-Creatine Malate’s structure aims to support those chasing more power without some of the bloating that sometimes pops up with monohydrate. Malic acid, a part of the combination, connects to energy production during short, explosive movements. In practice, most users expect similar strength gains and improved endurance, especially across sets of weightlifting or sprints.

Despite the buzz, overdoing creatine never leads to better results. Extra grams get flushed out and might upset the stomach. Hydration helps keep things running smoothly, so water intake must match the higher intensity workouts this supplement tends to invite.

Everyone processes supplements a bit differently. I’ve watched some people thrive on standard doses, while others scale back to avoid cramping or gastrointestinal issues. People with kidney concerns, or who take prescription medicines, have an extra reason to talk to a healthcare provider before diving in. Large, long-term studies on Di-Creatine Malate specifically haven’t filled the journals yet. Most safety assumptions come from broader research on creatine in general.

Trust in reputable brands with clear ingredient lists, and skip anything that hides behind proprietary blends. I always suggest tracking energy, recovery, and any unwanted reactions in a journal for a few weeks after starting a new supplement. Many find real, quantifiable progress after several weeks, especially if nutrition and sleep remain on point. Consistency in daily dosing outweighs quick fixes or mega-doses.

Long-term studies comparing different forms of creatine could help highlight the true strengths of Di-Creatine Malate. Transparent lab testing, better consumer education, and open conversations between trainers, doctors, and athletes will keep pushing the field forward. Knowing your own body, reading up on current research, and keeping your daily routine dialed in—these steps support both safe and effective supplement use.

Walk into any gym, and you’ll spot at least a few tubs of creatine on the shelves. Di-Creatine Malate can stand out because it combines creatine with malic acid. Manufacturers claim this mix helps with solubility and digestion, making it an alternative for people who struggle with regular creatine monohydrate. Fitness forums have plenty of people sharing glowing reviews about muscle growth, recovery, and reduced fatigue. But it always makes sense to take a closer look—especially with supplements.

Plenty of folks use Di-Creatine Malate without any major issues, though some users share stories that echo my own past experience with creatine in college. The big one: water retention. Di-Creatine Malate seems to cause less bloating compared to monohydrate, but some people do report puffiness or a “soft” look, especially if their dosage goes above five grams a day. Upset stomach happens pretty often, too. Gas, cramps, and some nausea sometimes show up, especially if the supplement lands on an empty stomach.

One common concern goes back to kidneys. People with healthy kidneys usually don’t have much to worry about at recommended doses, but folks with any existing condition need to tread carefully. Creatine raises creatinine, a marker doctors often use for kidney health, which can make test results confusing. Doctors usually stress that this marker doesn’t automatically mean damage, but it highlights the need for transparency between users and healthcare providers.

My own experience and pretty much every discussion on supplement boards highlights the simple truth: more is not always better. Doubling up might just mean more cramps and repeated trips to the bathroom. Sticking with the dose shown on the product label or talking with a sports nutrition expert remains the best route. Splitting the dose, or mixing it with more water, can sometimes make a difference for sensitive stomachs.

Malic acid gives some fruit its sharp bite. It’s what separates Di-Creatine Malate from the more common monohydrate version. Some users mention slightly better digestion and less stomach trouble with Di-Creatine Malate, likely thanks to malic acid’s extra helping hand. At the same time, overdoing it can lead to its own set of issues—think loose stools or mild heartburn, similar to eating too much sour candy.

Supplements only fill the cracks in an already solid foundation. A balanced diet takes priority over any powder. Hydration matters here too. Any form of creatine, including Di-Creatine Malate, draws more water into muscles. Skipping water can crank up the risk of cramps or stomach issues. Reports of proprietary blends without clear dosing should encourage buyers to choose brands that publish ingredient amounts and get tested by third parties.

Anyone thinking about using Di-Creatine Malate gets more value by starting low and watching how their body reacts. Checking in with a healthcare provider, especially with any pre-existing health conditions, beats guessing games. Investing in a supplement that actually lists every ingredient and its amount helps avoid surprises. Drinking more water and spreading out serving times smooths out a lot of bumps in the road.

Di-Creatine Malate looks attractive on paper—less bloat and less stomach trouble, with similar performance benefits as classic creatine. Some side effects stick around for certain folks, and personal experience lines up with what research shows: quality, dose, and hydration make the biggest difference. Focusing on smart choices brings better results—not just in gains, but also in long-term health.

Step into any supplement store, and creatine, in some form, will usually greet you on the shelf. Di-Creatine Malate stands out these days, often touted for blending creatine with malic acid. Stores and gym regulars say it mixes better than the classic monohydrate and settles in your stomach with less bloat. It’s enough to draw a curious beginner, especially if someone wants all the benefit with fewer side effects.

Back in my earliest days of lifting, creatine monohydrate was the mainstay. Pay a few bucks, dump a scoop in water, and hope for a strength boost. With Di-Creatine Malate, one reason folks jump ship is stomach comfort. Some users find traditional creatine can upset the gut or pull in water, which leads to that notorious “bloated” feeling. Sometimes the aftertaste is tough. With the malate blend, the mix dissolves cleaner and feels lighter, and users like myself have noticed less cramping. Studies, such as those highlighted in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, suggest that the form itself isn’t what gives results—creatine content is. Di-Creatine Malate doesn’t outperform monohydrate in creatine delivered, but it does offer a different experience for folks who struggle with digestion or chalky drinks.

Purely on results, both forms deliver similar outcomes. The body needs creatine to recycle energy in muscles. Whether it’s attached to malic acid or not, the effect on strength and muscle is well-documented. The International Society of Sports Nutrition puts monohydrate at the top for proven effectiveness, and most research follows suit. The key factor is not the variant, but if someone takes it consistently and at the suggested daily serving of 3-5 grams. Di-Creatine Malate costs more per serving and isn’t any safer or riskier. Still, if someone feels better with it, the price might make sense on a personal level. No one wants to skip workouts from stomach aches.

In my own gym circle, new lifters often rush to stack up supplements. A solid routine, meals with real protein, and enough sleep will carry most of the load in the beginning. Supplements come after results from these basics slow down. Some beginners hope the right powder will replace hard work. No creatine can do that. Folks should remember, more expensive or fancier packaging doesn’t mean better results.

Safety is another point beginners should keep front and center. Both forms have strong track records for safety when used as directed by healthy adults. The kidneys process the same amount of creatine no matter the source. The only risk comes from overdoing it or not drinking enough water. The National Institutes of Health and major health organizations confirm these supplements don’t harm kidneys in healthy people when used responsibly. Still, anyone with pre-existing kidney issues or concerns should talk to a doctor before starting any form.

For most just starting, plain monohydrate works just fine. It saves money, goes into lots of research, and covers all the needs. Di-Creatine Malate can be a solid choice for anyone who’s tried monohydrate and felt off, can stomach the extra cost, or just prefers the taste and mixing qualities. I always tell new lifters to check labels for third-party testing and skip flashy promises. Real progress starts with barbell basics, not a scoop of powder.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Bis(2-{carbamimidamido}acetic acid) malate |

| Other names |

Creatine Malate Di-Creatine Malate Creatine Dimalate Malic Acid Creatine |

| Pronunciation | /daɪ-kriːˈeɪtiːn ˈmæleɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 68677-91-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3563206 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:132945 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3986983 |

| ChemSpider | 22864895 |

| DrugBank | DB11635 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03e0b37d-8a67-49d9-b051-1e47b2fc4f2e |

| EC Number | EC 202-718-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 1896785 |

| KEGG | C16045 |

| MeSH | Dicarboxylic Acids |

| PubChem CID | 24707157 |

| RTECS number | RR2740000 |

| UNII | 95UM64013N |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4048972 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C8H15N6O4·C4H6O5 |

| Molar mass | 372.38 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.29 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.28 |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~3.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | ~8.97 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | NA |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.570 |

| Dipole moment | 3.69 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 336.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. |

| Precautionary statements | P264: Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P270: Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. P301+P312: IF SWALLOWED: Call a POISON CENTER or doctor/physician if you feel unwell. P330: Rinse mouth. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 1, Flammability: 0, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): "2000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | Not Listed |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 3–5 g per day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Creatine Creatine Monohydrate Creatine Ethyl Ester Creatine Hydrochloride Creatine Citrate Magnesium Creatine Chelate Creatine Pyruvate |