Dicreatine citrate started gaining attention around the late 1990s, a period when sports nutrition really picked up speed in the U.S. and Europe. Researchers and athletes searched for forms of creatine with higher solubility and fewer digestive issues. This pursuit naturally led to experimenting with different salts of creatine. After creatine monohydrate dominated the shelves, complaints about bloating and cramping pushed supplement makers to blend creatine with several acids, eventually landing on the citric acid salt. My own experience in university labs during this era showed that stacking organic acids with amino acids was the direction to milder, friendlier products. Dicreatine citrate quickly won a following among both bodybuilders and endurance athletes looking for alternatives with smoother physical profiles.

Dicreatine citrate combines two creatine molecules with citric acid, forming a water-soluble powder. The ingredient provides both creatine and citrate in one scoop, appealing to those wanting more than simple monohydrate. Being a white or off-white powder, it dissolves quickly into water or juice. It sometimes tastes a bit tart, which is to be expected with the citric backbone. I’ve watched trainers recommend it in place of monohydrate, especially for folks who report stomach sensitivity.

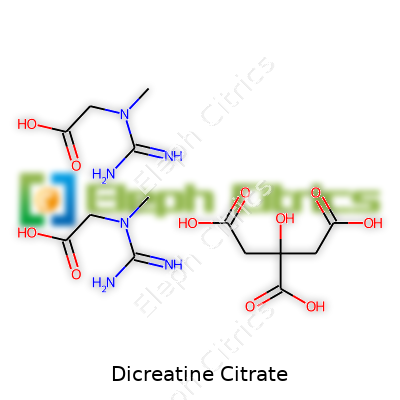

Physically, dicreatine citrate arrives as a fine, almost silky powder that clumps slightly in humid air. It mixes rapidly in liquids, creating clear or slightly hazy solutions, depending on water temperature and purity. Chemically, it carries creatine’s familiar guanidinoacetic structure, bonded with citric acid at both the amino and carboxyl ends. This double linking kelps the salt more stable against hydrolysis and humid storage conditions. Lab tests put the melting point around 220°C, and it gives a neutral to mildly acidic pH in water. Shelf life remains long as long as the powder stays dry and shaded from light. Its molecular formula typically appears as (C4H9N3O2)2.C6H8O7.

Manufacturers commonly offer dicreatine citrate in 95–98% purity, with heavy metal content under 10 ppm and microbial counts within food-grade standards. Each batch comes with a certificate of analysis confirming creatine content per serving, absence of banned substances, and manufacturing under GMP protocols. Labels often state total creatine provided per gram, followed by instruction on dosage—usually one to two teaspoons per day, equalling 3–5 grams of total creatine. It's not unusual to see supplementary advice for hydration, reflecting creatine’s mild diuretic pull. Allergen declarations and “not intended for people under 18” warnings turn up in fine print to meet supplement regulations across the U.S. and EU.

Making dicreatine citrate is a straightforward salt-forming reaction. In practice, manufacturers start with pharmaceutical-grade creatine and dissolve it in water along with citric acid monohydrate. The reaction shifts at room temperature, and the product then precipitates out or crystallizes as the solution cools. Filtration and drying at low heat complete the process. This avoids the need for harsh organic solvents or high temperatures, keeping byproducts low. I’ve seen the same approach used on the pilot scale with little change from the lab protocol. Post-processing, the powder moves to packaging in nitrogen-flushed bags to cut down on oxidation.

The structure resists both enzymatic breakdown and spontaneous cyclization that plague some other forms of buffered creatine. The presence of citric acid modifies the rate at which creatine absorbs in the stomach, possibly easing the spike that sometimes sparks nausea. Chemists have managed to tweak the ratio of creatine to citrate, but the 2:1 balance holds up as the most stable and palatable form. Attempts to bond further with other acids, like malic or ascorbic, have hit roadblocks on taste or solubility, confirming citrate as the current sweet spot.

Dicreatine citrate goes by a handful of other names in both the nutrition and chemical industries. Some product lines call it “Creatine citrate” or “Creatine bicitrate,” while lab catalogues sometimes stick with its IUPAC name: bis(2-(carbamimidamido)acetic acid) citrate. Popular supplement brands market it under proprietary names, but the label’s small print usually reveals “dicreatine citrate.” Ingredient lists often abbreviate to DCC.

Safety studies so far support dicreatine citrate’s clean record, reflecting the established history of both creatine and citric acid in the human diet. In regulated labs and plant settings, operators follow standard powder containment and respiratory protection rules. Dust inhalation can irritate mucous membranes, but skin or eye contact rarely brings severe effects. Storage protocols require cool, dry rooms and sealed, food-safe containers. Equipment must stay free of cross-contact with allergens. Finished products depend on ISO, GMP, and HACCP certifications to reassure both regulators and everyday buyers of their trustworthiness.

The sports nutrition market absorbs nearly all of the dicreatine citrate produced, but biomedical research has started to explore its impact beyond the gym. Most users dissolve the powder in water just before exercise, aiming for faster recovery, bigger lifting gains, or sharper cognitive function. Some recovery drinks use it for its acidity and taste profile, blending better than the chalky monohydrate. Researchers tracking athlete physiology report smaller spikes in creatinine excretion and fewer cases of muscle cramping when compared with older creatine versions. Though approved as a supplement in the U.S., individual countries in Europe and Asia still wrestle with debating its registration as a novel food ingredient.

A growing body of research digs into not only the athletic benefits but also the cellular effects of dicreatine citrate. Recent clinical trials compare absorption rates and bioavailability with monohydrate, suggesting that the citrate form sustains higher serum creatine levels for a longer period. Academic labs also use dicreatine citrate to study metabolic health in populations with chronic fatigue, sarcopenia, and some neurodegenerative conditions. From my own background in sports labs, trainers and participants consistently prefer citrate-based creatines for smoother pre-workout mixes and mild taste. Innovation comes mostly through efforts to combine dicreatine citrate with ingredients that support mitochondrial health, aiming to treat more than just muscle decline.

Acute and long-term toxicity studies anchor the ongoing debate about supplement safety. Animal and limited human trials put the median lethal dose massively above any real-world serving. Side effects rarely exceed digestive upset, usually when users overconsume or fail to hydrate. Chronic studies pay close attention to kidney function, since creatine metabolism produces creatinine. So far, no evidence links dicreatine citrate, at recommended levels, to kidney abnormalities in healthy adults. A few older patients with pre-existing kidney disease receive warnings not to use it without medical oversight. Most published work confirms that the added citric acid does not increase risk of gastric ulcers compared to other food acids.

Recognizing the success of dicreatine citrate in sports, supplement manufacturers have started to study modified versions for new targets. Researchers will likely start exploring tweaks in molecular structure to boost absorption or to pair it with slow-release minerals and vitamins, widening its reach to older adults and those managing chronic muscle-wasting conditions. Regulatory trends push toward clearer labeling and traceability, so seeing blockchains applied to supplement origin tracking wouldn’t surprise industry insiders. Universities and biotech startups continue partnering to explore synergies with plant-derived bioactives or probiotics, aiming to launch the next generation of “smart” sports nutrition ingredients. Most signs point to a future where dicreatine citrate takes a key spot in recovery, cognitive, and anti-aging formulas as the industry puts focus on not just muscle, but the brain and full-body resilience.

Dicreatine citrate slips under the radar for a lot of people shopping in the supplement aisle, yet it pops up more often for athletes and people who track their workout recovery. Tough gym sessions take more than willpower. Someone serious about fitness usually has a shelf littered with tubs and bottles, always looking for something that makes a real change in the way their body feels after exercise. Creatine in any form has gained a loyal following for a reason. It helps muscles refuel between sets—something you feel in the gym, not just read on a label.

This form—dicreatine citrate—combines creatine with citric acid, giving the powder a different flavor profile while promising benefits for muscle energy stores. Unlike older forms that clump or don’t dissolve easily, dicreatine citrate mixes better in water. That small upgrade touches daily routines that anyone using shaker bottles notices right away. The stuff tastes less chalky, and it spares you the gritty mouthfeel that can come from some plain creatine supplements.

Bodybuilders, sprinters, and strength athletes gravitate toward creatine because it helps with repeated bursts of effort. Anyone who’s just lifted their final rep knows the struggle of burning muscles. Some folks claim dicreatine citrate feels easier on the stomach than creatine monohydrate. People like me have tried both. For some, stomach cramps put a pause on any progress, so finding a gentler option matters.

Even among recreational lifters and weekend warriors, the demand for supplements that mix clean and digest well never lets up. No one wants to spend the afternoon bloated and sluggish after a morning workout. From direct experience, swapping to dicreatine citrate made it easier to stick to a training plan since I didn’t lose energy dealing with indigestion.

Creatine has a mountain of research behind it—benefits for power, muscle growth, and even brain health. Research focuses mostly on monohydrate, the gold standard, but dicreatine citrate brings its own promise. People want effective delivery and high absorption, not just another powder. Citrate may help by making the supplement mix better and potentially absorb faster, but the research isn’t as deep yet.

It’s smart to look past marketing claims. Not every difference between types of creatine leads to a leap in results. Personal experiences and some independent studies point to fewer complaints about water retention and stomach discomfort. No one supplement fixes everything, but options like dicreatine citrate help more people get the benefits of creatine without dropping their routine due to side effects.

Trust in a supplement builds over time—reading ingredient lists, checking for independent third-party testing, tracking lab results, and listening to personal cues from the body. Health professionals and trainers understand that what works for one doesn’t always fit another, so trying different forms like dicreatine citrate becomes part of the journey, not a shortcut.

Supplements, especially those promising an edge in physical performance, always work best paired with honest effort, sleep, and smart nutrition. Tools like dicreatine citrate support hard work, but nothing replaces consistency in lifestyle and training. Anyone jumping on the bandwagon should start slow, read plenty, and maybe keep a log behind that next bottle of powder. It’s not about chasing hype—it’s about finding steady, real support for the path you are on.

Supplements line the shelves in every gym or health shop. People hunt for anything that brings an edge, especially with muscle and performance. Dicreatine citrate often gets lumped in with the muscle-building crowd. Behind every new powder is a question: does it really help, and does it come with a risk?

Plenty of fitness fans consider it a cousin to regular creatine. Some feel less bloated with dicreatine citrate than monohydrate. Brands often promise better absorption or a smoother stomach. After training for years with different supplements, I’ve noticed that most gym-goers want to avoid any stomach troubles or discomfort during their sessions. People swap brands all the time until something feels right. For them, feeling good often matters as much as a scientific benefit.

Studies on creatine tell a good story, since creatine itself counts as one of the most researched supplements. Most people handle it well in reasonable amounts. Dicreatine citrate’s main difference from monohydrate is the addition of citric acid, which gives a slightly tart taste and possibly easier mixing. Even with that change, the body breaks it down to creatine and citrate in the stomach. So far, no wave of side effects specific to dicreatine citrate has shown up in published research or consumer reports. A lot of evidence about creatine in general carries over, since the body ends up dealing with much of the same stuff.

Anyone with healthy kidneys should process extra creatine without much trouble. Too much, though, can make people feel a bit off. Some report cramping or loose stool with massive amounts, but not everyone reacts the same. The main issues come up for people with pre-existing kidney disease. For anyone in doubt, a chat with a doctor beats any opinion from the supplement aisle.

Supplements fall into a tricky space because health agencies don’t inspect every container before it hits the shelf. Some companies take shortcuts, and impurities or undisclosed ingredients sometimes sneak in. Lab testing from independent groups like NSF or Informed Choice can make a big difference. If a supplement carries their seal, it’s been checked for purity and banned substances. That’s real peace of mind if you’re competing in sports, or just want to be sure about what goes into your body. In my experience, people who care about results never want their hard work derailed by a tainted product.

No one supplement changes the game for everyone. A balanced diet, steady exercise, and good sleep always carry the most weight. Dicreatine citrate just gives another option, especially if regular creatine upsets your stomach. People chasing a shortcut or ignoring underlying health issues won’t find an answer in any powder. For the curious, pay attention to how your body feels, keep portions sensible, and talk to a healthcare professional before starting something new. Safer choices grow from information, not hype on the label.

Dicreatine citrate has gained plenty of attention among athletes looking for a boost in power or muscular endurance. It’s a form of creatine bound to citric acid. Some folks claim it dissolves better and feels easier on the stomach than creatine monohydrate. But confusion about dosing crops up often.

Getting the amount right means seeing results without wasting money or dealing with unnecessary side effects. Too much and a person risks digestive issues, dehydration, or extra burden on the kidneys—especially when underlying health conditions already exist. Too little, and it’s just another powder that won’t do much.

Most research on creatine sticks to monohydrate, but a handful of studies show that dicreatine citrate probably works best at similar daily amounts. Taking 3-5 grams each day hits the mark for most people aiming to saturate muscles over time. I remember starting low, watching for any bloating or weird stomach feelings. Most users can avoid discomfort by working up to a maintenance dose over a week.

A loading phase—the practice of taking larger doses for a few days—has become less popular. For folks who want results quickly, loading with up to 20 grams in four divided doses for five days followed by a daily 3-5 grams can be used. But it’s just as effective for strength and muscle gain to use a regular single dose every day for three to four weeks.

It’s tempting to double up, thinking more is better. Extra doesn’t turn into more muscle or energy. The kidneys clear excess creatine through urine, so most just goes to waste. Anyone who’s ever dealt with cramping from overzealous supplement use knows it’s simply not worth it.

Mixing dicreatine citrate with plenty of water helps reduce potential for stomach pain. Taking it alongside food or a carbohydrate-rich drink can help absorption. Hydration always matters, but I’ve noticed on days I slack off drinking water, a supplement like this can make me feel crummier since creatine pulls water into muscles.

Individuals with kidney disease or any health condition need a healthcare provider involved. Supplements still aren’t regulated like medications, so checking for quality and purity makes a difference. Reputable brands will publish third-party test results to back up their claims.

Counting on quick fixes almost always disappoints. Most folks chasing performance keep supplements simple and steady. Sticking with 3-5 grams per day, through both training blocks and rest days, helps build up muscle creatine stores and maintain them. Regular routines and listening to the body go a lot further than swinging wildly between doses.

No magic trick exists with dicreatine citrate. Quality sleep, regular workouts, balanced meals, and attention to hydration all boost what creatine can do. Supplements can support hard work, but nothing replaces it. Knowing the right dose turns something promising into a real, useful part of an athlete's toolkit.

Walk into any supplement shop and you’ll find a shelf lined with tubs promising muscle, strength, and better workouts. Dicreatine citrate has picked up attention because it mixes creatine’s proven benefits with a dose of citric acid, which helps it dissolve better in water. People see the word “creatine” and often think improved athletic results with little risk. That’s not a bad starting point, but the full story stretches a little further.

Many folks who try dicreatine citrate feel it in the gut first. My own first go with a creatine blend involved some surprising stomach rumbles during a busy gym session. It’s not rare for creatine to pull more water into the intestines, and that often means some bloating, gas, or the quick need to find a bathroom. One review in the Journal of Dietary Supplements notes that many people share these complaints, especially when taking bigger scoops.

Citric acid can add to that discomfort for anyone sensitive to acidic foods. Acid reflux, mild burning in the throat, and cramping pop up in forum threads and research surveys alike. Drinking plenty of water can make a difference. Smaller servings, spread over the day, help limit these complaints for those who want to stick with dicreatine citrate.

Creatine moves water into muscle cells. That’s a good thing for muscle growth, but it also shifts how the body manages water and electrolytes. I’ve seen athletes load up on creatine, forget to drink more water, and then complain about cramps during high-intensity workouts. The American College of Sports Medicine points to dehydration as a risk if users don’t keep up with fluids. Dicreatine citrate might blend easier than regular creatine monohydrate, yet the need for hydration stays the same.

Most people with healthy kidneys process creatine just fine. Still, any supplement puts a little extra strain on organs that filter waste out of blood. People with kidney trouble—whether diagnosed or not—should talk with a doctor before using products like dicreatine citrate. The National Kidney Foundation reminds folks that even over-the-counter energy boosters can worsen hidden conditions. Seeing a doctor and adding routine blood tests can catch potential issues before they turn serious.

Plenty of athletes use more than one supplement, and some also take prescription meds. Herbal products, caffeine-filled preworkouts, and anti-inflammatory drugs often work against or amplify creatine’s effects. One example: anyone on diuretics risks further dehydration with daily creatine. The FDA hasn’t taken issue with dicreatine citrate in healthy adults, but it’s smart to double-check everything with a healthcare provider, especially if chronic conditions or prescriptions play a role.

Listen to the body and make changes along the way. Start with half a serving instead of a full scoop. Drink extra water, as much as matches sweat and thirst. Pairing creatine—including dicreatine citrate—with carbs can lower stomach trouble for some. If something feels off—persistent pain, swelling, or more than the usual soreness—stop and get professional guidance.

The best plan involves doing research, talking with health professionals, and tracking how the body reacts. Dicreatine citrate offers a smooth mix and a promise of more reps in the gym, but real progress depends on smart, careful choices—and paying attention when side effects show up.

Talk about sports supplements with any gym regular and creatine comes up fast. Most people know about creatine monohydrate because it's cheap, easy to find, and helps lift a few more reps. Dicreatine citrate sounds fancy but slips under the radar for most athletes. If you ever checked out ingredient lists and paused at citrates versus monohydrates, here’s what’s actually going on and why it matters.

Dicreatine citrate blends creatine molecules with citric acid. Chemically, that changes how it interacts with water and your body. It tends to dissolve faster in water, often leaving behind less grit at the bottom of the glass. If you’ve gagged on clumps or had a chalky aftertaste from monohydrate, that mixability makes a difference. No one wants to force down a gritty shake after leg day.

Some supplement companies talk about improved absorption. There’s a theory here: citrate forms might get into your bloodstream a little faster because of how they break apart. That said, independent studies haven’t found huge leaps in muscle creatine levels versus monohydrate, at least not enough to rewrite how everyone trains. Real-world results show you don’t need “superior uptake” to get stronger over time.

People sometimes get stomach discomfort with creatine monohydrate, including bloating or light cramps. Dicreatine citrate seems to be gentler on digestion according to user reports and some clinical notes. For athletes who keep a food log to avoid sidetracking their sessions, a product that goes down smooth catches attention. You end up more likely to stick to your routine.

Look at the price and you’ll notice dicreatine citrate often costs more than monohydrate. Since years of research back up monohydrate’s effects, many experts recommend starting there to track results against your wallet. Premium options need to prove something special to justify the cost. Citrate’s real benefit mostly leans on taste and stomach comfort, not big gains in pure strength.

Supplement contamination can cause trouble, especially in sports where banned substances end careers. Dicreatine citrate sometimes comes in flavored blends marketed as “advanced” or “premium.” Always check for third-party testing (NSF, Informed-Sport) to avoid fillers or risky batches, no matter which creatine form you reach for. A clean label protects your reputation and health far more than any cool molecule structure ever will.

Every athlete has preferences and quirks. If you need to save money and rely on proven science, monohydrate holds up. If digestive issues keep you from hitting your macros or sticking to your routine, dicreatine citrate has a place. For some, taste alone makes the choice, especially for those who toss a scoop into their daily shake and ride out the year. Weigh your priorities—budget, stomach, flavor, or just habit. The best creatine keeps you training longer and harder, whichever type sits on your kitchen counter.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-[Carbamimidamido-N-(carbamimidoylcarbamoyl)glycino]acetic acid; 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid |

| Other names |

Creatine citrate Creatine 2-(hydroxytricarballylate) Dicreatine citrate |

| Pronunciation | /daɪˈkriː.eɪtiːn ˈsɪtreɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 54940-97-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3507983 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:74972 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3707268 |

| ChemSpider | 14236670 |

| DrugBank | DB14537 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 19d77897-bcf0-4f6d-ac99-aa3946ac28f8 |

| EC Number | 218-611-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 1693137 |

| KEGG | C18336 |

| MeSH | Dicarboxylic Acids |

| PubChem CID | 11760728 |

| RTECS number | GF8775000 |

| UNII | P6V7Z416F7 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C8H17N6O7 |

| Molar mass | 418.40 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.9 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -2.8 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.13 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 3.7 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.55 |

| Dipole moment | 8.7 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 494.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -2490.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A11EA |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory tract, eye and skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Flash point | Flash point: 160°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): >2000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 4646 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | Not Established |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 3 g |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Creatine Creatine citrate Creatine malate Creatine monohydrate Dicreatine malate |