People have been experimenting with iron salts for centuries, long before terms like “supplement” or “chelation” hit textbooks. Iron deficiency became common knowledge after the industrial age, driving research into compounds that help the body absorb this tricky element. Early formulas included everything from iron filings in wine to crude acetate blends. Research led to better ideas: organic acids, like citric acid, grab iron, keep it soluble, and make it easier on the gut. Ferrous citrate didn’t really take off until chemists figured out how to get pure, stable product in the mid-1900s. By that point, healthier iron sources meant fewer side effects and better control. Medical journals talked up ferrous citrate as an option for folks who couldn’t handle sulfate or gluconate pills.

Ferrous citrate offers a water-soluble way to get iron into food, beverages, or medical products. It comes as a pale green powder or granules, stable at room temperature, and with a tang that comes from its citric acid foundation. Commercially, you’ll see it marketed under various names, often skipping the “ferrous” label altogether for less intimidating branding. Some companies coat tablets for better taste or to protect against moisture, but the active compound does all the heavy lifting.

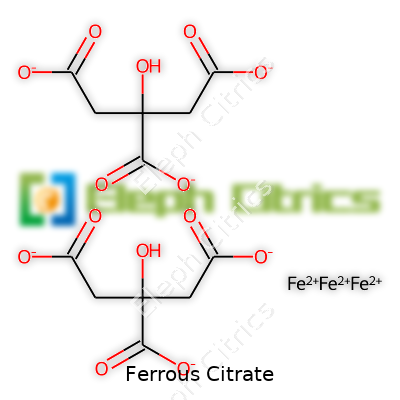

In the lab or on the shelf, ferrous citrate keeps things pretty straightforward. It presents as a fine, nearly odorless powder, sometimes picking up a greenish hue due to its iron content. Its solubility in water isn’t extraordinary, but it dissolves enough for food fortification and tablet prep. The iron in its +2 oxidation state gives it the power to help with hemoglobin without oxidizing into the less useful ferric form if exposed to air for short periods. Its molecular structure pairs one iron atom with three molecules of citrate, giving it a relatively low toxicity compared to other iron salts.

Industries working with ferrous citrate keep a close eye on quality—nobody wants to risk inconsistent dosing. Specifications cover iron content, purity, pH, moisture, and absence of heavy metals. Pharmacopeias lay out expected concentration ranges—usually around 20–24% elemental iron by weight. Labels list both the chemical and sometimes the brand variant to minimize confusion. Any supplement or food product manufacturer who values trust includes clear guidance about dosing and storage, with warnings for accidental overdose—a real concern with iron compounds, especially in households with children.

Making ferrous citrate doesn’t require rare materials or exotic reactors. The standard process combines ferrous sulfate (an industrial staple) and citric acid in water, adjusting the pH to favor citrate over other forms. The solution slowly converts as the iron reacts with the carboxylate groups on citric acid, forming a bond that keeps the iron ready for biological use. Filtration, drying, and milling follow, often in a controlled environment to avoid accidentally oxidizing the product. Quality control steps in at every stage to avoid batch variations and accidental contamination.

Ferrous citrate reacts predictably: acids can break it down, strong bases might cause precipitation, and oxidizers push iron to ferric state, which loses some of its therapeutic kick. In biology, this matters because the gut environment can swing pH or introduce oxidizers. Some labs tinker with the chemical backbone, introducing substituents or stabilizers into the citrate portion, mostly to improve absorption or slow degradation in food prep. These tweaks promise better bioavailability or longer shelf life, though any change attracts extra scrutiny from regulators.

One trip down any pharmacy aisle or supplement website and you’ll notice a slew of aliases—iron(II) citrate, citrate of iron, ferric-citrate (in error, sometimes), and even creative marketing names. Labels might say “chelated iron with citric acid,” which means the same compound in most cases. This cloud of synonyms reflects both branding games and efforts to dodge customer confusion about the relationship between elemental iron and its chemical partners.

Working with iron compounds means thinking about accidental exposure and toxicity, but ferrous citrate comes with fewer side effects than harsher iron salts. Standard operating procedures cover dust control, hygiene, and spill cleanup. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and similar regulators keep iron exposures in check, especially where powdered material travels by air. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rules call for clear batch records, precise mixing, and verification of iron content per serving. Accidental ingestion by children gets the most attention, pushing manufacturers toward safe caps and unmistakable warning labels.

People know ferrous citrate best as an iron supplement used to treat or prevent anemia. Hospital pharmacies might add it to their roster when oral iron treatment is needed with less risk of constipation or metallic taste. Nutritionists point out its place in fortified cereals, plant-based milks, and health bars. Manufacturers aiming for clean-label products use ferrous citrate to slide past metallic off-tastes and stomach upset associated with sulfates. Animal feed makers also see value here, boosting livestock growth and health quietly in the background. Some water treatment operations dabble in ferrous citrate to tie up unwanted metals or scavenge oxygen.

Labs and universities test new delivery forms, blending ferrous citrate with vitamins or antioxidants, trying to ramp up absorption rates. They keep chasing ways to mask the iron flavor or bypass digestive barriers. Clinical studies track absorption, stomach upset, and the body’s overall response. Each year brings announcements about improved chelates, new excipients, or micronized powders that hit the bloodstream faster. The focus keeps shifting toward reducing side effects and dosing frequency. Social programs and health officials, especially in regions hit hard by anemia, keep watch for breakthroughs that drive down costs and make iron supplements more accessible.

Iron poisoning, especially in children, haunts every discussion about iron supplementation. Ferrous citrate has a lower toxicity profile than many other salts when taken as directed, but nobody ignores the risk posed by accidental overdose. Toxicology studies track serum iron levels after ingestion, assess organ impact, and map how the compound breaks down in different conditions. Product recalls or redesigns often trace back to these studies, which help guide manufacturers toward safer units, better packaging, and clearer education for the public. The FDA and similar agencies in other countries publish detailed monographs, ensuring that every lot of ferrous citrate undergoes safety checks before it leaves the plant.

Looking ahead, the need for affordable and gentle iron supplementation still sits at the top of public health priorities, especially with shifting diets and an aging population. Researchers and manufacturers aim to fine-tune formulations that put less strain on the stomach, taste better in foods, and dissolve quickly in water. Sustainable process tweaks draw attention, with more companies hoping to cut energy use, minimize waste, and source greener ingredients. Health advocates push for broader use in low-income regions where anemia stunts development and weakens communities. The next generation of ferrous citrate products promises better safety, simpler use, and more reliable health impacts, making this familiar compound a backbone of both medical and nutritional solutions.

Ferrous citrate shows up on supplement shelves as a source of iron, a mineral the body relies on for many critical jobs. Many recognize iron from childhood nutrition lessons: it keeps our blood strong, it helps the body transport oxygen, and it fuels our energy levels. Some people don't get enough iron from diet alone, so health professionals recommend iron supplements to bridge the gap.

Growing up with family members who struggled with anemia gave me an up-close view of what happens when the body falls short of iron. Fatigue that doesn’t get better with more sleep, shortness of breath from basic activity, and a strange craving for ice or dirt are a few classic signs that something’s off. Medical experts point out that iron deficiency is the most common nutritional deficiency worldwide. The World Health Organization estimates that over 30% of the world’s population suffers from anemia, which often traces back to low iron.

Ferrous citrate lands on the list of iron supplements that aim to tackle this problem. Its combination of iron and citric acid supports absorption in the intestines, helping the body use what it takes in. The citric acid also lessens the chance of constipation compared to more traditional forms like ferrous sulfate, which helps people stick to their supplement routine without uncomfortable side effects.

Iron supplements like ferrous citrate matter for more than one group. Pregnant women top the list, since pregnancy boosts iron needs; not enough iron puts both mother and child at risk. Young children and teenagers hit rapid growth stages, which means extra iron demand. People who avoid animal products, such as vegetarians and vegans, also benefit since plant-based diets deliver less easily absorbed iron. Those with medical conditions that cause blood loss, like heavy periods or gastrointestinal bleeding, often depend on iron supplements to avoid slipping into deficiency.

Doctors don’t hand out iron pills like candy. Blood tests confirm low hemoglobin or ferritin before anybody writes a prescription. Taking extra iron without medical advice sometimes leads to overload, damaging organs over time.

Ensuring that iron makes it onto the plate starts at the family dinner table. Lean red meat, beans, lentils, spinach, and fortified cereals belong in any iron-rich meal plan. The body grabs more iron from food when paired with vitamin C—think orange slices with breakfast cereal or bell peppers with lentil soup.

For cases where diet alone doesn’t make the cut, supplements like ferrous citrate step up. Some clinics partner with nutritionists to educate patients about food sources and make testing more accessible. Community health programs can help by providing free or discounted iron supplements to pregnant women and young children in high-risk areas.

Not all supplements use the same kind of iron or dosage, and side effects like stomach upset can make some brands tough to tolerate. Pharmacists and healthcare providers appreciate ferrous citrate for its gentler touch on the digestive system, which often means better follow-through.

Quality matters, too. Purchasing supplements from companies with transparent manufacturing standards keeps unwanted contaminants out of the equation. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration keeps a watchful eye on supplement safety, though not all products earn the same trust.

By bringing attention to iron deficiency and the practical ways to handle it, people can support their families and communities. Ferrous citrate represents one approach in the bigger picture of health, nutrition, and self-care—reminding us that small steps, like taking the right supplement, add up over time.

Iron earns its place as an essential mineral in the diet. It plays a role in carrying oxygen through the bloodstream and supports many biochemical reactions in the body. Low iron leaves you tired, less able to focus, and more likely to experience health issues over time. Ferrous citrate brings iron into the body in a form that’s easier to absorb, helping people who struggle with traditional iron supplements or who have digestive sensitivities.

Doctors prescribe Ferrous citrate mostly for those with iron-deficiency anemia or diagnosed low iron. Swallowing the tablet with water is usually enough, but iron interacts with other things you eat and drink. Based on experience and what healthcare professionals say, it works best when taken on an empty stomach. That means taking it about an hour before meals, or two hours after. Food can slow down or limit iron absorption, and calcium-rich foods, coffee, tea, and some whole grains can reduce its effectiveness even more.

Vitamin C helps the gut absorb iron, so an orange, glass of juice, or a vitamin C tablet alongside the dose can make a big difference. Some people feel sick to their stomach or deal with other side effects when taking iron on an empty stomach. If that happens, take the supplement with a small meal or a snack to make things easier to handle. It’s better to take the full amount with a little food than to skip doses because of discomfort.

Iron has a habit of causing constipation or mild stomach cramps. Drinking more water and adding high-fiber foods like vegetables, oats, or berries can help. People sometimes switch from tablet to liquid forms if they have trouble swallowing pills or digesting them. Splitting the prescription into two doses during the day may cut back on stomach problems for some people.

Stick with the recommended dose. More is rarely better with iron. Large amounts over time can damage organs and bring on other medical problems. Iron overload feels a lot like low iron at first—tiredness, joint pain, and odd skin changes—so following lab checks with the doctor helps keep things on track.

Reliable advice often comes from a doctor, pharmacist, or dietitian. These professionals know how other medicines or supplements interact with iron and can offer guidance that fits personal health needs. Reputable organizations—such as Mayo Clinic, the NHS, or registered health authorities—keep their guidance up to date and based on current research, which makes their advice reliable.

People dealing with low iron sometimes share tips on online forums and support groups about which products work best and how to cope with side effects, but always double-check personal anecdotes with a trusted medical source. What works for one person might not fit another’s situation.

Building new habits around a supplement feels tricky at first. Setting daily reminders, linking the dose to a regular activity, and tracking side effects in a simple notebook or phone app make the process manageable. This structure helps avoid missed doses and makes it easier to share details with your healthcare provider during check-ups. Taking Ferrous citrate feels less daunting with small adjustments—protecting health, energy, and long-term wellbeing in the process.

Ferrous citrate, an iron supplement, shows up in many medicine cabinets. It gets used by people dealing with low iron levels or iron-deficiency anemia. The goal is simple: help your body make healthy red blood cells so oxygen keeps flowing. But as someone who struggled with anemia in college, I learned that iron pills—no matter the brand—sometimes bring more than just a little boost in energy.

Most folks who start taking ferrous citrate experience digestive issues quickly. Nausea, stomach cramps, and gas can all join the ride, often within hours of the first dose. My doctor recommended taking the pill with a meal, saying it’s easier on the stomach. Still, I found even then that I felt queasy for half an hour or so. For some people, the discomfort gets bad enough to skip doses, which means iron levels don’t get back to normal. I read that constipation—sometimes severe—hits a lot of people using any iron supplement, including ferrous citrate.

An article from the Journal of Clinical Medicine pointed out that iron supplements commonly cause gastrointestinal side effects in up to 70% of users. There’s no way around it: if you expect zero trouble, you might end up disappointed. Sometimes, the bathroom scale tips in the other direction and diarrhea happens instead. Taking the pill at different times of day or with plenty of water sometimes helps, but everyone’s body reacts a little differently.

If you spot darker stools, don’t panic. Iron, especially in ferrous form, tends to darken bowel movements. The first time I saw this, I got worried. My pharmacist calmly explained that this is not blood—just a side effect of the supplement. Metallic taste in the mouth can also pop up for some users. It may linger for hours, making your morning coffee taste odd, which I remember well from my semester on iron pills.

Taking more than the recommended dose never speeds up recovery and can be dangerous. Too much iron in the system—iron overload—damage organs over time, especially the liver and heart. Severe overdose in children can be life-threatening. This is not just theory; reports from the CDC mention accidental iron poisoning as a recurring problem in families with young kids. Make sure bottles get stored far from little hands.

Ferrous citrate may impact how other medicines work. Some antibiotics, thyroid pills, and antacids lose their punch when mixed with iron supplements. I still remember a family member whose thyroid disease wasn’t under control until her doctor realized the timing between doses mattered. Besides medicine, some folks feel allergic to certain ingredients in iron supplements. Swelling, rash, or trouble breathing demand quick help from an emergency room.

Doctors agree that pairing iron with vitamin C-rich foods can improve absorption. Small tips like splitting doses or switching to a slow-release version can cut the worst side effects. Foods that are rich in iron—like beans, spinach, or red meat—also help. Blood tests every few months ensure treatment is working, without causing harm.

Always stay in touch with a healthcare provider before starting or stopping iron supplements. Side effects are common, but with the right plan, they don’t have to disrupt your life.

Pregnancy often brings a flood of questions, and diet starts to feel more complicated than ever. Iron usually finds itself near the top of the list. Moms worry about getting enough iron, especially since blood volume goes up and babies rely on mom’s supply. Physicians tend to prescribe iron supplements, yet a long list of versions on the pharmacy shelf might make anyone pause—what’s the difference, and is ferrous citrate in the mix of safe options?

Ferrous citrate falls into a group of “iron salts.” Doctors used to reach for ferrous sulfate out of habit, but newer forms like ferrous citrate or ferrous bisglycinate started showing up for a reason. They often cause less stomach trouble—less constipation, less nausea. For a pregnant woman already fighting off morning sickness and food aversions, that softer landing can feel like a small win.

Scientific research tracks iron needs closely; the World Health Organization and CDC both recommend daily iron for pregnant women, about 27 mg. Iron helps prevent anemia, lowers risk of preterm birth, and supports brain growth for the baby. Ferrous citrate can deliver on these goals because, at the end of the day, the body mainly wants elemental iron. Getting enough is more important than the particular compound, as long as it’s a reliable option and the gut can handle it.

No over-the-counter supplement should get the green light without considering both benefits and safety. Studies so far haven’t raised warning flags about ferrous citrate compared to the old standbys like ferrous sulfate or ferrous gluconate. Many prenatal vitamins include alternate forms of iron for this very reason—they hope to make supplement routines easier to stick with, especially for those struggling with digestive side effects. Research supports the safety of iron salts in pregnancy, including ferrous citrate, as long as they’re taken within medically recommended amounts. Over-supplementing carries its own risks, like giving the liver too much work to do and spiking blood pressure.

It’s easy for expecting parents to spiral in the supplement aisle. I’ve been with family members who scrolled through their phones in a panic, wondering whether that newer label was safe. Trust often comes from direct conversations with doctors, not just an endless feed of internet advice. I remember how one OB spent extra time explaining the breakdown: the body just wants absorbable iron, and some folks simply tolerate one form better than another.

Guidance from medical teams matters. Blood tests measure iron and ferritin, not the supplement brand, and these results usually lead the conversation. A doctor might change recommendations if iron levels fall or digestion suffers. Pregnant women deal with enough decisions, so they often welcome guidance that links science to daily life. Seeing family and friends work with their doctors, I’ve noticed that consistent communication helps ease fears, whether they choose ferrous citrate or another iron source.

Choosing supplements isn’t just about the label—it’s about finding what works in real circumstances. Options like ferrous citrate open the door for those who just couldn’t stick with old-school iron pills. Still, doctor supervision remains the backbone of safe pregnancy care. Keeping a close eye on lab results, learning which form feels best, and asking questions at appointments can turn confusion into confidence. Iron matters, but so does the trust we build with medical experts guiding the journey.

Iron sits at the core of our body's oxygen transport system. Without enough iron, things start to feel heavy—fatigue, shortness of breath, a cloudy mind. Ferrous citrate steps up as one of the options for boosting iron when diet alone isn't keeping up. It blends iron with citric acid, making it a supplement that's easier on the stomach than some alternatives.

People always ask for a single number, a universal dose that works for anyone. Health just doesn’t run on a fixed schedule like that. It depends on age, gender, medical history, current iron levels, and even dietary habits. The average adult struggling with iron deficiency usually lands around 50 to 100 milligrams of elemental iron per day, based on guidance from trusted sources like the CDC and National Institutes of Health. Since ferrous citrate only contains a portion of that as true "elemental" iron, a tablet labeled 200 mg usually provides 45 to 50 mg of elemental iron.

Children and older adults need different dosages. Pregnant women face higher iron demands, so their needs jump—often 27 mg of elemental iron a day, but some are advised to take more. Experience says it pays to check your actual iron levels first and see what your body truly requires. Overloading with iron can spark side effects, including stomach pain and constipation, or in rare cases, iron overload.

The body only absorbs what it needs. Excess iron doesn’t just slip away—it builds up, straining the liver and increasing long-term health risks. There have been reports where high doses taken for long stretches have led to organ damage or worsened bacterial infections in those with weakened immunity. Good care means cleaning up your diet but also keeping supplements in line with exact needs.

Iron doesn’t work alone. Vitamin C helps increase absorption, while coffee, tea, and some whole grains can interfere. People often see better results by spreading their dose apart from meals, sometimes with a glass of orange juice. Taking Small consistent doses has proved less harsh on digestion than a single large dose each day.

Start with a blood test for ferritin and hemoglobin—not a hunch. Then discuss results with a trained professional who knows iron supplementation inside and out. Regular checks show how things change over time and head off any complications. Do not skip this step, even for “natural” supplements, because iron acts powerfully in the body.

People treating chronic conditions or taking other medications, especially blood thinners or certain antibiotics, must be extra careful. Mixing iron supplements with other pills without medical advice brings real risks.

It makes sense to track iron intake from both food and supplements, fine-tune dosages based on regular labs, and never play guessing games. Iron helps at the right dose and right time, and can cause real harm if those rules go ignored. Listen to the body, track the numbers, and rely on guidance from experienced healthcare providers.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | iron(2+) 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate |

| Other names |

Iron(II) Citrate Ferrous(2+) citrate Iron citrate Citrate de fer(II) C6H6FeO7 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈsɪ.treɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 19743-92-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3569531 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75831 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1200980 |

| ChemSpider | 185141 |

| DrugBank | DB14641 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.033.416 |

| EC Number | 220-652-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 14638 |

| KEGG | C18726 |

| MeSH | D018729 |

| PubChem CID | 16211023 |

| RTECS number | NO4560000 |

| UNII | 9CJ0Y1PVU5 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5090836 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H5FeO7 |

| Molar mass | 244.97 g/mol |

| Appearance | Reddish brown powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.8 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | sparingly soluble |

| log P | -1.3 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.2 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Magnetic susceptibility (χ) of Ferrous Citrate: +1300 x 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 3.87 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 286.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | B03AA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid breathing dust. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use with adequate ventilation. Keep out of reach of children. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 1070 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 2400 mg/kg |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ (as Fe) |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Ferric citrate Iron(II) sulfate Iron(III) chloride Ferrous fumarate Ferrous gluconate Ferrous sulfate Iron(II) lactate |