Lactic acid has been around as long as fermentation. Early farmers noticed milk sometimes turned sour and thickened into yogurt or cheese, but they didn’t have names for the molecules causing this. Chemists eventually isolated lactic acid in the late 18th century, starting with Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. The industry really took off after people figured out bacteria could turn sugars into lactic acid, not just in dairy but also pickles, sauerkraut, and even silage for animal feed. Large-scale production kicked in during the 20th century, especially as companies spotted opportunities to use fermentation tanks to churn out bigger, purer batches for both food and industrial uses.

Lactic acid brings more than just that familiar tang in sour milk. Available as a clear liquid or a white crystalline powder, this molecule steps beyond food and into medicine, cleaning, textiles, and even biodegradable plastics. Companies supply it in various purities, either as a blend of left- and right-handed molecules (racemic mixture) or just one, depending on whether the end use lands in pharmaceuticals or plastics. Food-grade lactic acid usually sits in the 80-90% concentration range, bottled carefully to keep it stable. Industrial types can go higher because most cleaning and textile uses don’t need the food-level scrutiny.

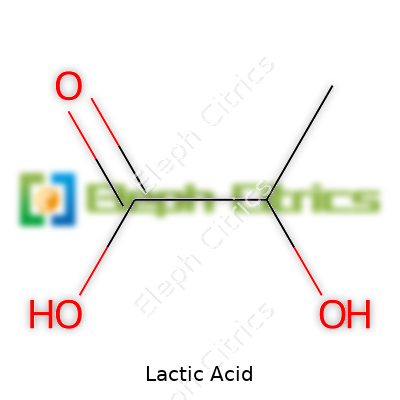

Lactic acid, C3H6O3, looks harmless—colorless, almost syrupy. It dissolves easily in water and ethanol, giving off a mild odor that’s hard to pin down unless you've sniffed old yogurt too many times. The melting point falls near 17°C for the pure stuff, so it stays liquid at room temperature in most places. It likes to give up its hydrogen ion, explaining the name “acid” and making it useful in adjusting pH. It blends readily with water-based mixtures, which matters for recipes, medicines, and formulations that need precision.

Labeling for lactic acid spells out its concentration, purity, and which version sits inside—L, D, or racemic. Food-grade shipments come with specs showing compliance to FAO/WHO Food Additive standards or the US Pharmacopeia, so buyers can check residue levels, heavy metals, and other contaminants. Industrial lactic acid usually comes with SDS (Safety Data Sheets) laying out physical properties, recommended handling, and any hazards. Some countries demand batch records for food and pharmaceuticals, chasing traceability from raw plant sugars or dairy all the way to the finished drum.

Production today uses either fermentation or chemical synthesis. Most fermentation plants feed sugars from corn, beets, or molasses into tanks, then let specialized strains of Lactobacillus bacteria chew through them. Temperature and pH controls help these bacteria stay focused on making lactic acid rather than booze or gas. Chemical routes break down acetaldehyde or lactonitrile, but the world prefers fermentation since it’s more sustainable and fits the biosafe trends. The real challenge comes in purification—removing other acids, starter proteins, salts, and getting down to the clear, marketable liquid food makers want.

Lactic acid’s structure makes it ideal for conversion into lactates (like those found in sports drinks) or for linking up into long chains known as polylactic acid (PLA), which turns up as compostable plastics. The acid group wants to react with bases, forming salts, and the alcohol group opens doors for esterification—turning it into flavors or fragrances. In the lab, chemists stretch lactic acid into more complicated molecules, adapting it for solvents, green cleaners, and even biodegradable sutures in medical settings. Fermentation tweaks and chemical modifications continue to widen the range of products that start from simple lactic acid.

Lactic acid turns up on ingredient lists under all sorts of names: E270 (as a food additive), 2-hydroxypropanoic acid (in technical literature), or even milk acid. Industrial product catalogs throw out names like “lacticum acidulant” or “fermentative lactic acid.” Each name comes with a context—food, pharmaceuticals, cleaning supplies—and it’s common to see labels drop the “D-” or “L-” prefix, leaving buyers to guess unless they check the spec sheet.

Used properly, lactic acid is as safe as the yogurt in the fridge. Its natural origin makes it attractive for “clean label” food products, but concentrated solutions need respect. Splashes can sting eyes or skin, and inhaling mists won’t do any good for lungs. Food processors and chemical factories rely on personal protective equipment (PPE), eye washing stations, and proper ventilation to keep the workplace safe. Regulatory bodies set limits on how much lactic acid can go into different foods, usually based on toxicology studies that look at what the body can break down easily.

You don’t have to look far to find lactic acid in action—pickles, yogurt, toothpaste, skin peels, biodegradable cups, even some medical drips. In foods, it adjusts tartness and preserves freshness. In cleaning, its acidity dissolves lime scale and sanitizes surfaces. PLA-based plastics, made from polymerized lactic acid, offer plant-based alternatives to petroleum plastics for bags, cups, and food containers. Veterinary medicine uses lactic acid to keep animal feed stable and safe, while pharmaceutical companies rely on it to adjust pH for injectables and syrups.

Much of the current research aims for greener, more cost-effective fermentation processes and higher yields. Scientists keep hunting for bacteria that work faster or tolerate higher sugar concentrations without shutting down. Some labs explore genetically engineering yeast or bacteria to create enantiomerically pure lactic acid, which helps PLA plastics set stronger and break down predictably. Developers also keep searching for better purification methods, cutting down on chemicals and wastewater, sometimes turning waste residues into biogas or feed.

Toxicologists have studied lactic acid for decades, since our own muscles make it during exercise. Low and moderate food-grade intakes pass through the body naturally. Problems only show up at concentrated exposures, with too much acidifying the blood (lactic acidosis) or irritating tissue. Food safety authorities like the European Food Safety Authority and the FDA have set clear Acceptable Daily Intakes (ADIs) based on animal and human studies. People with rare metabolic disorders, such as lactic acidosis or certain enzyme deficiencies, experience greater risk at high exposures, but these conditions remain rare. Most everyday uses fall well below those limits.

The future looks busy for lactic acid, as “green chemistry” and bio-based materials pick up steam. PLA plastics need even purer lactic acid, driving better fermentation and separation technology. Food companies keep looking for more natural ways to preserve and flavor products, so lactic acid stays in kitchens and factories. Some countries invest in turning agricultural waste into lactic acid, cutting costs and greenhouse gas emissions. Medical device makers keep tinkering with lactic acid polymers for slowly dissolving implants and drug-release systems. As more customers ask for plant-based, sustainable, safe ingredients, lactic acid stands ready for new challenges—shaped by centuries of discovery and innovation, but now with an eye on the climate and consumer comfort.

People hear “acid” and sometimes expect trouble. Yet lactic acid got its start in something less scary: sour milk. Ancient beauty routines already involved milk-baths, Cleopatra wasn’t just after a soak—she wanted smoother skin. Lactic acid falls under a group called alpha hydroxy acids, which help lift dead skin away so the healthy stuff underneath shines through.

Exfoliation feels like a skincare buzzword, but the real goal’s straightforward: get rid of built-up layers, reveal fresher skin, help products absorb. Lactic acid doesn’t scrape or cause microtears like gritty scrubs. It works by breaking down old cells, giving dull faces a smoother texture and brighter look. Dermatologists have measured this benefit: studies show regular use boosts cell turnover, which can soften fine lines and fade age spots over time.

Many people use glycolic acid to exfoliate, but that option can strip moisture. Lactic acid acts differently. Because its molecules are larger, lactic acid doesn’t dive as deep. That’s good news for anyone who’s tried chemical exfoliants and wound up red and dry. Instead, lactic acid attracts water to skin’s surface, boosting hydration. Studies in clinical journals back this up, showing that low concentrations even help skin barrier function.

Personal experience counts, too. After using lactic acid in the evenings, my cheeks no longer felt tight. There wasn’t any burning or peeling, just softer skin—no surprise, since it’s gentle enough for sensitive folks when used sensibly.

There’s more to lactic acid than cosmetic perks. People with keratosis pilaris—the bumps on arms and thighs—find improvement from regular use. Dermatologists often recommend it for rough, dry patches, even on elbows and heels. By removing dead cells and drawing moisture in, lactic acid smooths these trouble zones.

For people living in dry climates, or for those in middle age facing slower cell renewal, lactic acid offers a bit of daily repair. Skin takes a lot, from sun, wind, and stress. Giving it a boost means fewer clogged pores, a finer surface, and less struggle against stubborn flakes during winter.

Start slow. Anything strong can irritate skin, especially in high doses. Many over-the-counter products contain lactic acid between 5% and 10%. Skip daily use at first—try it twice a week. Evening is best. Always follow with moisturizer and use sunscreen every morning. Lactic acid can make skin want to soak up the sun’s rays, leading to new spots if left unprotected.

Not all lactic acid products feel the same. Some serums include extra moisturizers or calming ingredients, which help cushion any tingle. Lotions and cleansers might suit people nervous about irritation. Each option invites experimentation and learning, something everyone does while finding what works for their skin.

No single ingredient fixes every problem. Lactic acid delivers gentleness, exfoliation, and moisture, but pairing it with consistent sunscreen, nutritious habits, and patience delivers the best results. Even low-tech solutions can have real impact, as the humble origins of lactic acid show. Listening to skin day by day tells you what to embrace, what to back away from, and how to keep moving toward healthier skin.

Skincare shelves overflow with promises, and lactic acid labels shout about glow and smoothness. People with sensitive skin often stop short. Every magazine warns about chemical peels, and one bad patch test can send someone back to bland face washes forever. Lactic acid is not a newcomer. This alpha hydroxy acid (AHA), derived most often from sour milk or fermented vegetables, has been used since ancient times—Cleopatra was famous for her milk baths. The hope is to nudge off a layer of dead skin, uncovering something softer underneath.

Most sensitive skin stories are built on hard lessons. A new product stings, burns, or leaves red marks. The concern with lactic acid is pretty clear: Will it irritate even more, or does it have a place among the calming oat milks and barrier creams? Sensitive skin reacts quickly. The skin barrier, the body’s natural wall keeping all the bad stuff out and the good stuff in, often works overtime but still shows cracks.

Lactic acid has a larger molecular size than its cousin glycolic acid. Molecules like this move more slowly through the top layer of skin. Less rush means less chance of harsh tingling and flaky patches. Studies have shown that lactic acid hydrates while exfoliating. That sounds odd for an acid—it’s supposed to dry things up, right? But this acid actually draws in water and helps hold it. That’s one reason many dermatologists recommend low-concentration lactic acid for dry, sensitive faces instead of stronger AHAs like glycolic.

I’ve tried cheap and expensive bottles over the years. The drugstore lactic acid mask at 5% tingled at first, but after a few minutes, skin felt softer—no tomato red aftermath. The high-end serum at 10% required careful spacing in my routine, a little like adding lemon juice to a stew drop by drop. A friend with eczema chose a 5% lactic acid lotion designed for children, recommended by her dermatologist, and had no issues at all.

Dermatologists back up these experiences with real data. Clinical trials comparing 5-10% lactic acid creams to plain moisturizers show that both groups saw smoother, less flaky skin. The lactic acid group often reported no extra discomfort—even among people who call their skin sensitive. One key, of course, is that these trials used low percentages and tested on freshly cleaned skin, not on top of open sores or after a retinol binge.

Sensitive skin often thrives with a gentle touch. My dermatologist recommends starting with 5% lactic acid no more than twice a week. Look for hydrating formulas with few other actives, and patch test before going all in. Skip rough scrubs, avoid sun exposure after applying acids, and always use sunscreen, since new skin gets sunburned more easily.

Quality matters, too. Cheap options sometimes load up on fragrance or alcohol, which stings more than the acid. Finding fragrance-free, simple formulas makes side effects much less likely. Lactic acid can gently remind sensitive skin that it can glow, too, without tears or regret.

Sensitive skin can get along with lactic acid—just on its own terms. Small doses, low concentrations, and simple routines give the best chance of gaining smoothness without backlash. Medical advice beats internet hype every time, especially for people with a track record of redness or allergies. For folks willing to dip a toe into the acid pool, lactic acid could be the mild solution hiding among the scary-sounding ingredients.

Lactic acid sounds more like something from a chemistry set than a bathroom shelf, but it plays a serious part in today’s skincare. It breaks down dead skin, which helps with smoothness and boosts the look of fresh skin. People who want brighter skin without going to the dermatologist every month reach for these chemical exfoliators, thinking they’ve unlocked a shortcut to healthier skin.

Loading up on acids without thinking through the details isn’t a smart move. I’ve known eager friends who didn’t respect this stuff and spent weeks covering up angry red cheeks. Overuse doesn’t just bring stinging and flaking, though—it can wreck your skin’s protective barrier. Dry patches, breakouts, and even sun sensitivity creep up quickly for those who treat exfoliation like a daily event.

If you’ve never used any sort of acid before, starting two or three times a week makes sense. Many dermatologists recommend this gentle approach. Jumping up to nightly use on the first day ramps up the risk of trouble. For myself, using a lactic acid product every three days kept my skin clear without the stress and burning I got with daily applications.

Frequency depends on what you’re using, too. Masks with high concentrations of lactic acid serve as once-a-week treatments. Serums meant for everyday use contain much less, so using them a few times per week fits many routines. If your skin stings, sheds, or grows red, dial it back and add moisture with a bland, unscented cream. Constant sun protection, especially SPF 30 or higher, is non-negotiable since acids lower your skin’s natural defenses against UV rays.

What works for your friend’s oily face might not suit sensitive skin. My own experience taught me that my cheeks prefer a single weekly treatment with stronger formulas, while my forehead can cope with weaker acids twice as often. Those with eczema or rosacea need to be extra cautious—sometimes skipping acids altogether feels best.

Younger skin, or folks who rarely use retinoids or scrubs, can easily get away with a once or twice weekly routine. If you spend more time outdoors or work in dry winters, this puts your skin under extra stress. Lactic acid becomes a twice-a-month ritual at most in these circumstances.

The main goal isn’t just exfoliating more often—it’s doing it smarter. Paying attention to your own face after each use makes a difference. If you see a glowing improvement, keep that rhythm. If the only thing you get is more dryness or itchiness, that’s your answer to slow things down.

The appeal of faster results draws a lot of people to experiment with frequent use, but gentle persistence beats over-experimentation. Start slow, check your skin’s signals, and remember that good skin comes from consistency—not from forcing nightly peels.

Most folks slip up and overdo it at least once. If this happens, take a break, use a mild cream, and let your face rest. Aiming for a long-term glow means giving your skin time to recover, not pushing it to the limit.

Lactic acid has earned a spot in a lot of skincare routines. It handles rough patches and dullness by sloughing off dead skin. Still, it also raises a big question: can it actually play nice with all the other powerhouse ingredients packed into modern routines?

From personal trial and error, combining lactic acid with every new serum out there doesn’t go smoothly. I’ve stood in front of my bathroom mirror more than once, wondering why a trusted serum suddenly stings or leaves my skin patchy. Mixing lactic acid with other strong actives, especially other acids or straight-up retinoids, ramps up the irritation. Sunscreen protects, sure, but doubling up on exfoliation has never led to glowing skin for me. Most dermatologists agree: overloading your skin with aggressive actives disrupts the barrier and invites breakouts or flaking.

Some combinations work. Hydrating ingredients like hyaluronic acid or gentle, soothing niacinamide pair well. For most people, layering these right after lactic acid feels calming, not punishing. My skin especially thanks me for a niacinamide serum after an exfoliating night; less tightness, less redness, more bounce. Simple moisturizers rich in ceramides also support the recovery process so that lactic acid can work without leaving skin raw.

Things turn dicey with other active acids. Pairing glycolic acid or salicylic acid with lactic in a single session turns exfoliation into an all-out assault. Even a tough face doesn’t benefit from being stripped. I learned the hard way: red, uncomfortable skin means dial things back or spread them out. The “one in the morning, one at night” pace allows active ingredients to deliver their perks without the backfire. Alternating nights helped me keep both exfoliation and clarity without the scaling effect.

Vitamin C and lactic acid both promise even tone and radiance but can cancel out each other’s strengths because each demands its own pH range. My experience pairing these serums within the same application led to more irritation than glow. Mixing them feels like chasing results that rarely arrive—stacking too many acids together often overwhelms the skin’s defense. I save vitamin C for mornings, shielded by sunscreen, and keep lactic acid for a couple of nights a week. The results don’t come faster, but they do last longer, and the balance means fewer setbacks.

Both retinol and lactic acid target texture and wrinkles, just from different directions. Using them on the same night is a recipe for trouble. My go at this led not to firmer skin, but to peeling and breakouts that took a week to fix. Dermatologists often push for alternating retinol on one night and lactic acid on another, giving skin a breather. Proper moisturization afterwards maintains results and minimizes flares. That method has never let me down.

A steady skincare routine works better than racing through the latest active ingredients. Reading what your skin can actually handle, and spacing out strong actives, prevents the kind of setbacks that make you want to quit. Hydrating and soothing products always make good sidekicks for exfoliating acids. The biggest lesson for anyone diving into actives is this: more isn’t better, and a patient, simple approach keeps your skin healthier in the long run.

Walk down any drugstore aisle, and you’ll find lactic acid in creams, cleansers, masks, and serums. It pops up in products for softening rough heels and promises smoother, brighter faces. But everything that works well for some people can come with downsides for others. Before I ever tried a single-pump serum, I heard lactic acid chalked up as “super safe” because it’s found in milk and even the human body. Then a friend explained her itchy, red rash after one use, and my view got a little more complicated.

Lactic acid belongs to the alpha hydroxy acid (AHA) family, and these acids act like a gentle sander on rough surfaces. Even gentle doesn’t always mean trouble-free. Sloughing away dead skin layers sometimes leaves new skin exposed, making it easier for sun, wind, or even tap water to cause irritation. Many people, including some dermatologists I’ve spoken with, say lactic acid causes less discomfort than stronger acids like glycolic. That’s only true until someone overuses it or pairs it with another exfoliating ingredient.

When side effects show up, they’re not dramatic—no one’s skin peels off in sheets. It’s more about sensitivity. Redness, a mild burning sensation, itching, and mild swelling show up, especially for those with eczema, rosacea, or otherwise reactive skin. Sometimes just a single application triggers tightness, small bumps, or a tingly rash. In my own experience, a light hand prevents these problems, but the temptation to layer and “help” rough skin fades fast with a harsh reaction.

People run into lactic acid in other places too—food preservatives, pickles, and even supplements for athletes. Using it in a skincare routine means accepting that certain people get hit harder by side effects than others. If a product goes near eyes or lips, stinging ramps up quickly. Some have even told me about cracks at skin folds, especially when using lactic acid on larger areas like elbows or feet. These issues don’t just fade after a gentle rinse.

One major point is the risk of increased sensitivity to sunlight. Skin becomes more prone to sunburn, and getting a bit lazy with sunscreen after a chemical exfoliation session can leave you vulnerable to redness or long-term pigment changes. According to research in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, regular use of AHAs like lactic acid can up sunburn risk by nearly 18 percent. It’s more than a scare statistic—it’s backed up by hours spent at the beach and regret after skipping SPF.

What’s the answer here? I’ve learned to tap into patch testing, especially when using a new product. Using smaller amounts at lower concentrations and skipping a day or two between applications lowers the chance of waking up with scaly cheeks. Mixing lactic acid with occlusive or soothing creams helps buffer irritation. Using moisturizers that contain ceramides or niacinamide offsets dryness. Most importantly, sunscreen every morning keeps those acid-treated skin cells covered where it counts.

If problems keep cropping up, switching to another exfoliating method or seeking advice from a dermatologist avoids months of guessing. Our skin can tell us plenty—spotting a trend in stinging or redness offers a cue to ease up.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-hydroxypropanoic acid |

| Other names |

2-Hydroxypropanoic acid Milk acid L(+)-Lactic acid DL-Lactic acid L-Lactic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈlæk.tɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 50-21-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3539533 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:422 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL42659 |

| ChemSpider | 503 |

| DrugBank | DB04526 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03d206ae-b6b4-44bb-9518-0939e2b676c2 |

| EC Number | 200-018-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 783 |

| KEGG | C00186 |

| MeSH | D001101 |

| PubChem CID | 612 |

| RTECS number | OE2450000 |

| UNII | 7T1F30V5YH |

| UN number | UN3265 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H6O3 |

| Molar mass | 90.08 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless to yellowish, syrupy liquid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.21 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| log P | -0.62 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.08 mmHg (50°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.86 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 15.1 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Paramagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.428 |

| Viscosity | 62.0 cP (25 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.41 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 86.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -694.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1367 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX01 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | WARNING |

| Hazard statements | H314: Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P301+P330+P331, P305+P351+P338, P310 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 112°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 380°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3543 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 3,730 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | # NIOSH: OD9625000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 50 ppm |

| REL (Recommended) | 50 mg/kg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 30 ppm |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sodium lactate Calcium lactate Potassium lactate Ethyl lactate Lactide |