Discovery usually marks the starting point for new doors in chemistry, and malic acid followed its own path. Early chemists first pulled it out of apple juice back in the late 1700s. At that point, it wasn’t easy to get and required a steady hand and patience. Over the next century, as analytical tools sharpened, researchers realized malic acid popped up throughout the plant world—grapes, tomatoes, rhubarb. It basically became recognized as one of the main reasons fruit tastes tart. Throughout the mid-1900s, new methods started to take shape for extraction, and by the late 20th century, malic acid made its way from lab curiosity to an ingredient in food technology, medicine, and industrial applications.

Malic acid usually appears in two forms: the naturally occurring L-isomer (L-malic acid) and the racemic mix (DL-malic acid) made by synthetic routes. L-malic acid plays a direct role in fruity and sour flavors, while DL-malic acid finds use in more technical applications. These forms aren’t just old news in the chemical world—they have practical reasons to exist side by side. L-malic acid dominates in foods and beverages, since people have built up experience with its taste and metabolism in nature. Because DL-malic acid comes from lab synthesis, industries lean on it for things like adjusting pH in manufacturing or as a chemical precursor.

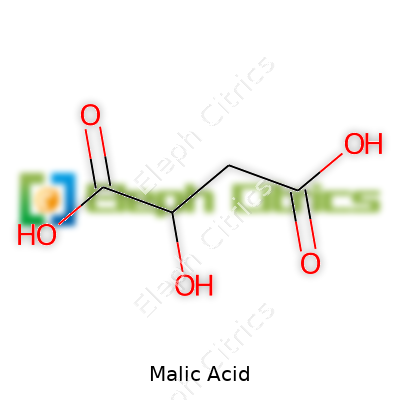

Malic acid comes as a white, crystalline powder. It dissolves easily in water, which matters for beverage and pharmaceutical applications since quick mixing keeps processes smooth. Its melting point sits around 130°C, and it gives off a distinctly sharp, clean taste. Structurally, malic acid carries two carboxylic acid groups and one hydroxyl group. This combination lets it function as a mild acid and a reducing agent. That chemical behavior forms the backbone for many reactions, including its place in the citric acid cycle. With a molecular formula of C4H6O5 and a molecular weight of about 134.09 g/mol, it packs a punch in almost any product needing acidity, preservation, or flavor.

On packages and shipments, regulatory demands ask producers to label malic acid precisely. They show content purity—generally above 99% for food-grade uses—along with water content (typically less than 1%). Color and clarity should show no visible contamination, since dark or dusty products signal problems. Food standards ensure correct labeling, mentioning “E296” in Europe and “INS 296” elsewhere, and batches must register under GMP and HACCP protocols. Companies print batch numbers, expiration dates, and storage instructions right on the bag or drum, leaving no room for error. Such standards help everyone down the supply chain trust the source, avoid mix-ups, and respond quickly if a recall or safety notice ever emerges.

Industries make malic acid on a large scale by hydrating maleic anhydride, usually with the help of catalysts and controlled pressure. Chemists found in the early 1900s that this process scaled up more easily than extracting from fruit. L-malic acid shows up naturally during fruit ripening, but extracting it from apples would never keep up with demand for candy, soda, and supplements. Another route involves enzymatic synthesis using fumarase, shifting fumaric acid into L-malic acid, but this approach limits production speed and cost efficiency. Synthetically-driven production gives industry the muscle to keep prices steady even as food and drink makers launch new sour-flavored products or tweak recipes.

Malic acid’s two carboxyl groups and one hydroxyl group set the stage for its widespread reactivity. It slides into esterification reactions to make esters with strong and pleasant fruit scents for the perfume industry. Reduction can turn malic acid into other hydroxy acids. Oxidation transforms it into oxaloacetate—critical in mitochondrial metabolism. Chemists rely on its functionality for controlled reactions: for instance, malic acid can chelate metal ions, making it useful as a stabilizing agent for solutions sensitive to unwanted metal interactions. In winemaking, it goes through malolactic fermentation, where lactic acid bacteria convert malic acid into lactic acid, softening sharpness and improving mouthfeel.

Common trade names and synonyms for malic acid show up on technical sheets, safety documents, and ingredient lists: apple acid, hydroxybutanedioic acid, E296, INS 296, and DL-malic acid. Scientific circles use (±)-malic acid when referring to the racemic mix and (S)-malic acid for the naturally occurring L-form. Some companies choose proprietary blends and brands for their products, promising specialized purity or performance based on these core formulations.

Worker safety comes down to a few core rules. Personal protective equipment, including gloves, dust masks, and eye protection, shields employees from irritation—malic acid dust brings on coughing or eye watering. Storage needs attention, too. Keep sealed containers in cool, dry spaces away from incompatible chemicals like strong bases or oxidizers. Food factories and chemical plants document every shipment and production run according to ISO and local regulatory requirements. Audits and training keep processes sharp and employees safe from slips and mistakes. Handling spills focuses on sweeping up powder and thoroughly rinsing the area—malic acid won’t explode or catch fire easily, but high concentrations can damage surfaces or skin.

Malic acid gets poured into soft drinks, energy beverages, hard candy, gums, and jams to amp up tartness and tweak sour notes. Winemakers depend on it during fermentation, and brewers sometimes use it for pH control. Pharmacies add it as a flavoring agent to mask tough medicine aftertastes. Manufacturers use malic acid in personal care—for example, as a mild exfoliant in some skincare products. Beyond food and cosmetics, it stabilizes metal ions in industrial cleaners and descalers while contributing to biodegradable plastics. Its multi-functionality keeps demand high across food technology, chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and agriculture.

Recently, researchers explore malic acid’s role as a platform chemical for bioplastics. The push for sustainability places emphasis on green chemistry routes—biotechnologists work on bacterial production strains that turn biomass into specialty acids at lower environmental cost. Scientists in medical research check how malic acid interacts with cellular metabolism, signaling pathways, and disease processes, searching for new roles beyond its long culinary history. Investigation into encapsulation, slow-release delivery, and custom flavor design could expand its value in processed foods and pharmaceuticals alike. Although it’s an old molecule, new applications keep rising on the horizon as questions shift to materials science, bioavailability, and sustainable design.

Malic acid occurs naturally in many foods people eat daily. Studies confirm that, under approved use levels, malic acid stands as safe for human consumption, showing no genotoxic or carcinogenic effects. Toxicity arises only at extremely high exposures. Reports point to mild gastrointestinal irritation if large amounts get consumed in one sitting. Regulatory evaluations from FDA and EFSA give clear upper intake guidelines, making accidental overexposure during regular use nearly impossible in well-controlled environments. Continuous research watches for subtle long-term effects in vulnerable populations but thus far, clinical and animal models reflect the same low-risk profile.

Demand for malic acid keeps growing as consumers lean into sour candies, functional beverages, and clean-label food ingredients. Sustainability will influence future production routes, motivating biosynthetic pathways and renewable raw materials. New polymer applications might bring malic acid into packaging and medical devices, while advanced drug delivery and targeted nutrition could rely on its biocompatibility and solubility. Researchers in agricultural technology check its role as a biostimulant to improve plant health and stress response. As regulatory landscapes tighten, manufacturers focus on transparency, sourcing practices, and traceability to meet rising expectations for food safety and environmental stewardship.

Bite into a tart green apple, and you’ll meet malic acid. Many of us first notice this sharp tang in sour candies and orchard fruits long before thinking about what’s behind the flavor. Malic acid comes straight out of nature but also gets made for plenty of modern uses. Its role isn’t just about making your lips pucker, either. Beyond fruit, malic acid lands in everything from sports drinks to snacks.

Few people look at nutrition labels, spot malic acid, and wonder about it. Most let it fade into a list of ingredients, but it has a hand in taste, freshness, and even how bodies make energy. Food makers rely on its sharp flavor kick in hard candies, lozenges, and gummies. Unlike citric acid, it delivers a clean, slow-release sour note. For anyone chewing on a sour treat that seems to “last longer,” thank malic acid.

Step outside the candy aisle, and you’ll find malic acid still working hard. Bakers toss it into dough mixes to tweak acidity and balance flavors. Cheese makers add it in tiny amounts to craft tang in certain flavored cheeses, also helping lower the pH. Beverage companies use it to brighten flavors in juices or lemonades where the natural tartness falls short.

Sugar isn’t the only thing powering your muscles. Malic acid plays a quiet but crucial role in energy cycles inside cells. Scientists call this the Krebs cycle, a process every person depends on to turn food into fuel. You’ll even spot malic acid listed in some sports supplements and drinks because of research linking it to reduced muscle fatigue during workouts.

Beyond food, you’ll spot malic acid in skin care—often in facial peels and exfoliants, because it helps break down dead cells. Some brands favor it over glycolic acid because it’s milder while still freshening the skin. Oral health brands see value in its tartness too. It pops up in toothpastes and mouthwashes to boost saliva flow and keep mouths feeling clean after meals.

People worry these days about additives sneaking into food, but malic acid holds a strong safety record. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration counts it as “Generally Recognized As Safe” when used as directed. Natural forms, found in apples, go right into daily diets. Lab-made malic acid shares the same chemical structure, so the body treats it the same way. The Environmental Working Group gives it a low risk rating. Allergic reactions almost never crop up. Still, moderation is worth considering—eating a bag of ultra-sour candy can upset a stomach or make teeth feel sensitive.

Some folks ask if malic acid is vegan or gluten-free. Today’s production method usually ferments food starches with safe microorganisms, so it doesn’t carry risks for most food sensitivities. Always check labels, since other ingredients in the same snack may bring allergens.

Food trends shift, and consumers push for simpler, clean-label products. Malic acid helps lower unhealthy added sugars by dialing up flavor intensity with less sweetener. Innovators already experiment with malic acid in plant-based meats, where it replicates the tang of real meat or cheese. The quest for better tasting, longer lasting, and healthier snacks owes a lot to this small but mighty acid. Paybacks reach beyond the kitchen—malic acid shows up wherever freshness, energy, and flavor meet.

Malic acid brings that familiar tangy kick to many foods and drinks. Green apples get their sour boldness from it, and so do a lot of candies, fruit-flavored drinks, and some baked goods. It acts as a flavor booster and a preservative for good reason—it’s an organic acid, found in nature, but most of what ends up in packaged foods is made in factories. That fact makes some people pause, and it’s worth talking about why malic acid matters at all.

Food regulators take a tough stance on additives, and malic acid isn’t an exception. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labels it “Generally Recognized as Safe” for regular use in food. European food authorities agree. If a food ingredient ever ended up causing harm when people ate it under normal circumstances, it would get yanked from the market or slapped with serious restrictions.

The science says the body already knows what to do with malic acid. Cells use it as part of the Krebs cycle, which fuels metabolism. When eaten, malic acid either slips right into biochemistry or passes through the same as any other substance you’d get from fruit. Even for kids or for people with mild acid sensitivity, the levels in foods don’t pile up to dangerous doses. Most packaged products contain less than a gram per serving—a quantity the digestive tract can handle without trouble.

Just because a chemical exists in fruits doesn’t mean it’s foolproof. Sour candies or supplements with a strong dose of pure malic acid can sometimes cause mouth or stomach irritation. Anyone who’s eaten too many sour gummies and felt a tingle or soreness in their mouth has felt this effect. The acid can wear down tooth enamel if overdone, especially in children with softer enamel, so moderation is smart.

Concerns sometimes pop up about food additives being connected to health conditions or hyperactivity, but most of the evidence points away from malic acid as a culprit. There’s no strong data suggesting it causes allergic reactions or other chronic health issues. One study after another, including research out of the European Food Safety Authority, keeps finding the same thing: no meaningful risk for the general public when it’s used as intended.

I’ve cooked with malic acid in the home kitchen and tried it in DIY recipes. My own experience lines up with the expert consensus. Sprinkle a little in a drink or dessert and it wakes up the flavor without causing harm. Problems only crop up if someone swallows a spoonful or eats way more sour candies than anyone ever should. The amount used in culinary prep doesn’t compare to industrial wallop, and most people never notice it doing anything but making flavors pop.

Kids, diabetics, and people with compromised dental enamel do better avoiding handfuls of sour candies that pack in acid by the gram. The rest of the population, including those who avoid many food additives, don’t usually have to sweat malic acid sprinkled throughout the supermarket. If consumer groups push companies to reduce highly acidic junk foods, it’s a tooth health issue, not a systemic safety issue. Food safety standards in the US, Europe, and many Asian countries keep a well-trained eye on these numbers, which helps consumers eat with confidence.

Food science always keeps unfolding, but malic acid looks like one of the safer ingredients in an ingredient list full of unfamiliar names. With reasonable use and an eye on good eating habits, it earns its reputation as a safe way to add a punch of sour.

Malic acid shows up in many apples and pears, blending into the tart flavor you notice when you bite into fruit. People often talk about it like it’s only another food ingredient, but I’ve found there’s much more to appreciate about it. Nutritional science points out that malic acid plays a role as a natural energy booster—something those of us balancing work, family, and maybe a half-hearted commitment to jogging can relate to.

Living with fatigue sets people back, whether it’s mild or chronic. Research shows that malic acid helps the body convert food into usable energy. This isn’t just another supplement pitch. Enzymes rely on malic acid for a key step in the energy-making process inside cells. I’ve noticed when I keep my diet rich in fruits—especially apples—or add a supplement, I hardly get that afternoon energy crash. Not every benefit hits everyone the same, but feedback from others matches my experience.

Stiff muscles after a workout or a long day’s work can stop many people from staying consistent. Studies connect malic acid to muscle relief, especially when combined with magnesium. This combo seems to dial down muscle soreness and boost endurance. For someone like me who takes fitness slowly, the difference shows up over weeks. It doesn’t make pain disappear, but it lowers the bump in the road that stops a daily walk or another lap at the pool. There’s good reason doctors recommend malic acid for people managing fibromyalgia or chronic fatigue.

Malic acid gives sour candies their punch, but it’s not just flavor. Dentists look at malic acid as a step in oral care, helping saliva production. A dry mouth leads to cavities, but more saliva helps clean teeth and gums. Experience shows chewing sugar-free gum with malic acid helps freshen breath and protects against dryness.

Skincare relies on gentle exfoliation. My experience mirrors dermatology research—using products with malic acid softens rough patches and lightens dark spots after a few weeks. Skin tolerates malic acid better than harsher acids, especially for people with sensitive faces. It keeps pores clear and smooths the surface over time, leading to a fresher look without the burn that other acids cause.

Cooking benefits from a bit of malic acid as well. Adding it to homemade jams, drinks, or even pickled foods keeps the flavors crisp and fresh. I’ve tried it with homemade lemonade and the sour flavor comes through without overpowering everything else.

Considering all benefits, moderation remains key. The FDA gives malic acid the green light as a safe food additive. Fresh fruit delivers a natural amount so anyone worrying about overdosing won’t find it in an apple or glass of juice. Supplements or concentrated foods need some caution, as anything can start irritating the stomach if used to excess.

I’ve learned the value of checking with a nutritionist, especially for people adding new supplements. It’s less about trying the next health hack, more about harnessing what nature already put into many of our foods for centuries.

Take a bite out of a green apple and taste that punchy sourness. Malic acid gives sour candies their kick and bumps up tartness in plenty of drinks. It shows up naturally in fruits, gets used as an additive in processed foods, and even lands in some beauty products and supplements. Most people swallow small amounts day in and day out without a second thought.

Research points out that eating foods with natural malic acid doesn’t harm healthy folks. The compound even helps turn food into energy, one reason it gets studied for fatigue. Regulatory agencies watch food additives closely, and malic acid sits on the safe list in low doses. For nearly everyone, standard levels in a diet cause no problems.

Too much of anything can create a problem. Downing big doses of malic acid, especially as a supplement, may lead to discomfort. Some report digestive issues—think bloating, stomach cramps, or loose stools. Acidic content means it could aggravate heartburn or reflux for those already fighting those battles.

Sensitive teeth might not love it either. Acid can weaken enamel over time, and that’s true for malic acid in sour candies or fruit. Dental professionals warn about sucking too many tart treats, the kind that keep your mouth puckered for an hour.

A handful of people carry an extra risk. Anyone with an allergy to apples or other sources rich in malic acid could react. Swelling, itchiness, or trouble breathing demand a call to a doctor.

Some supplements promise better muscle function, more energy, or relief from certain health conditions. Malic acid plays a role in making energy in the body—laboratory studies support this idea. Though a few small studies hint that it could help folks with fibromyalgia when paired with magnesium, researchers need to dig deeper before making big claims.

Supplements can mean more concentrated doses than nature intended. People with kidney problems, for example, process acids differently, so talking with a healthcare provider before using concentrated malic acid isn’t optional—it’s crucial. People who already take lots of acidic foods or supplements risk throwing off the body’s acid balance.

If malic acid has a downside, it usually hides in excess or misuse. Moderation works for most people. Reading ingredient lists, choosing less processed snacks, and not overdoing sour candies or drinks pays off in the long run. For those thinking about supplements, asking a pharmacist or doctor makes sense. Healthcare providers can explain safe amounts, spot interactions with other medications, and flag issues tied to kidney or digestive health.

Dentists offer advice too. Chewing sugar-free gum or rinsing with water after eating sour foods helps protect tooth enamel. For anyone who feels digestive pain after certain foods, jotting down symptoms might shed light on a trigger—then adjustments can follow.

Fake promises and miracle cures have always been a risk in the supplement aisle. Real health improvements come from balanced diets, not from hoping one acid will fix everything. Staying curious, seeking honest information, and chatting with professionals help us keep risks low and health high.

Biting into a green apple or even a sugary gummy candy, you might notice a sharp, tangy kick. This taste usually comes from malic acid. In its natural form, malic acid shows up in fruits like apples and cherries. Some folks call it “fruit acid.” It isn’t some rare or exotic component—your own body produces it while turning food into energy through the Krebs cycle. So yes, malic acid exists in nature and inside your own system every single day.

Most processed foods calling for that “sour apple” punch rely on malic acid produced in labs. The reason goes back to price and consistency. Natural sources like apples only offer small amounts, making large-scale production impractical. Food makers and beverage companies land on synthetic malic acid, which mirrors the natural version down to the molecule. It’s made through chemical reactions involving substances like maleic anhydride derived from petroleum.

So, if the end result is the same molecule, does the source really matter? Well, this depends on what you value. Some shoppers look for clean labels, preferring ingredients they recognize from their own kitchens. Others care more about how something affects the body than where it came from. Nutritionally, both forms act the same, and the body processes them just as easily.

I often get questions about whether synthetic malic acid causes any harm. Regulatory groups like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have cleared it as “generally recognized as safe” for eating. There haven’t been red flags in research showing differences between eating malic acid from apples versus a powder stirred into sports drinks.

The main danger pops up in the quantities and combinations used in food. Overdoing sour candies or “acid” drinks can erode tooth enamel or upset a sensitive stomach, but this is more about portion size than the acid being natural or synthetic. Using moderation, just like with sugar or salt, keeps things in check for most healthy adults.

People say they want more honesty on packaging. Brands could respond by listing the exact source of malic acid—like “from apples” or “from fermentation”—so those who care can make informed choices. I notice more companies experimenting with fermentation to make acids using food-safe microbes, a process that skips around petrochemicals and might sit better with environmentally minded shoppers.

For anyone with allergies or who follows a strict natural-food lifestyle, checking with manufacturers or choosing unprocessed foods can help. Eating a fresh apple brings in natural malic acid with all the extra goodness—fiber, vitamins, texture—that no white powder version can truly match.

Industries could invest more in natural fermentation, cutting ties with oil-based chemicals. Governments and advocates can push food makers to explain sources more clearly. People can stay curious about what lands in their food. At the end of the day, it’s not just about molecules; it’s a question of trust, transparency, and personal values.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-hydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Other names |

Apple acid Hydroxybutanedioic acid DL-Malic acid 2-Hydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmælɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 617-48-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1720819 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17813 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL821 |

| ChemSpider | 890 |

| DrugBank | DB01306 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b871510b-4533-4dee-b02e-8c419229b9c3 |

| EC Number | EC 200-293-7 |

| Gmelin Reference | 6081 |

| KEGG | C00149 |

| MeSH | D008294 |

| PubChem CID | 525 |

| RTECS number | OJ7875000 |

| UNII | 817L1N4CKP |

| UN number | UN1789 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID3023872 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O5 |

| Molar mass | 134.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder or granules |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.601 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| log P | -1.26 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: <0.1 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 3.40, pKa2 = 5.20 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.92 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -23.0 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.570 |

| Dipole moment | 4.44 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 157.4 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -958.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1341.0 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA12 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | Estimated 398 °C (748 °F; 671 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 1600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Malic Acid: 1600 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | MA1750000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5000 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg bw |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Fumaric acid Maleic acid Succinic acid |