Potassium malate has a backstory that reaches back to the natural world. Malic acid, the stuff behind the tartness of apples and many other fruits, caught the attention of scientists in the late 1700s. Early chemists managed to isolate it from apple juice—hence the name malic—from “malum,” Latin for apple. Over time, the industry saw a need for better, more functional salts to use in foods, drinks, agriculture, and pharmaceuticals. That sent researchers exploring new ways to pair minerals with organic acids, and potassium malate was born. Experiments from the mid-20th century onward established a process for synthesizing it, and food technologists noticed its pleasant taste and buffering ability.

Potassium malate usually arrives as a white to off-white powder. It has both the tang of malic acid and the nutritional bump of potassium. Often, you’ll spot it in ingredient lists for drinks and snacks where manufacturers want to cut down on sodium or give sourness a softer edge. In agriculture, it helps keep fertilizers flowing or bolsters certain nutrient blends. Some pharmaceutical tablets use potassium malate to buffer acidity and support potassium intake, especially for folks aiming to manage blood pressure or balance electrolytes.

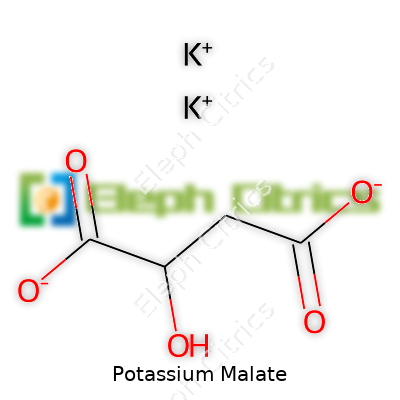

Potassium malate often shows up as a slightly granular powder. It dissolves in water much better than in alcohols. The compound is pretty stable at normal temperatures and humidity, which matters a lot for blending it into foods or pills. Chemically, its formula is C4H5KO5, combining malic acid’s organic side with potassium’s charge-balancing metal ion. Its pH tends to land near neutral when dissolved, making it gentle on both products and stomachs. In practice, this means manufacturers reach for potassium malate when they want a sour note that won’t throw off the acidity of the finished product.

Labeling and specifications have tightened up over the years. High-quality potassium malate comes with certificates of analysis listing potassium content, moisture limits (usually below 1–2%), and purity (often over 98%). Food safety laws in many countries focus on heavy metals, microbial load, and possible contaminants. European and North American regulators assign E-numbers (E351 in Europe) or INS numbers so that ingredient lists make sense across borders. Common labeling practice is simply “potassium malate,” unless it’s paired up in a blend, which has to be spelled out. That way, consumers or health professionals with dietary restrictions know what they’re getting.

Manufacturers tend to use a neutralization process. Start with malic acid—usually made by fermenting sugar with specific fungi. The acid then reacts with a purified potassium base, most often potassium hydroxide or potassium carbonate. This neutralization forms potassium malate plus water. Drying and milling yield a powder that’s easy to dissolve. The whole sequence follows good manufacturing practice rules, with tight control of temperature, pH, and process materials to keep impurities out and save on energy.

Potassium malate withstands storage pretty well, less likely to clump or break down unless you hit it with heat and moisture for long stretches. Unlike sodium salts, it won’t react with as many other minerals to form stones or insoluble compounds. Its carboxylate groups, the business end of the molecule, let it act as a good buffer, keeping pH from drifting in foods or solutions. Given the rise of plant-based and low-sodium diets, more people have asked chemists to tweak the molecule—maybe to create time-release forms or double salts with magnesium for special health uses.

You’ll hear potassium malate referred to as “dipotassium malate,” or just by its number in ingredient lists: E351. Other synonymous names include potassium salt of malic acid, and sometimes it gets bundled into multivitamin formulas or electrolyte drinks under branded terms like “potassium apple acid salt.” For pharmacists, chemical suppliers, or food scientists, these names make it clear what’s inside without mixing things up.

Safety remains a big deal for anyone dealing with potassium malate. The compound itself is considered non-toxic at levels typically found in foods and supplements. Still, potassium intake matters, especially for individuals with kidney or heart conditions. Manufacturers and processors keep to strict operating and documentation standards, watching every step for cross-contamination, especially from potential allergens. Workers handling bulk material wear gloves and dust masks. Industry standards often say to store the product in a dry, closed container away from heat or acids that might induce clumping or breakdown.

Most people meet potassium malate without realizing it. Beverage makers love it for giving a smooth tartness to fruit juices, sports drinks, and ready-to-mix powders. Reduced-sodium foods use it to bring a sharper flavor without bumping up the salt content. In the pharmaceutical world, it buffers stomach pH in some antacid and mineral tablets. Some crop fertilizers add potassium malate to help keep essential minerals moving freely in soil. Sports science labs look to it for potassium supplementation, helping balance the minerals lost in sweat. As plant-based diets gather steam, potassium malate shows up more often in vegan cheese, yogurts, and snacks, especially where flavor needs a bit more zip.

Research on potassium malate keeps moving, with scientists exploring its absorption in the body, its impact on metabolic alkalinity, and its ability to support kidney function without stressing sodium intake. Clinical studies in recent years compared it with potassium gluconate and citrate, checking blood levels and gastrointestinal tolerance. Food manufacturers sponsor work to refine taste profiles, cut costs, and make blends that deliver both potassium and malic acid at optimal ratios. Research partnerships between universities and the private sector look at eco-friendly production, biotechnological synthesis routes, and better analytical methods for ensuring purity at every batch.

Most studies show that potassium malate earns a good safety record. Animal studies using doses well above usual dietary levels find little or no toxicity. Regulatory agencies such as EFSA and the FDA set daily intake recommendations for potassium as a mineral to avoid overconsumption. The bulk of adverse effects tend to show up not from malate itself but from too much potassium in the diet, which can aggravate kidney problems or heart rhythms. Ongoing work in toxicology labs aims to flesh out how potassium malate acts in long-term dietary patterns and whether combinations with other acid salts change its effects.

Potassium malate looks set to fill growing needs for clean-label, functional ingredients across food, drink, and health products. More consumers read nutritional labels, looking for low-sodium options and potassium-rich alternatives. Biotechnology firms see room for pushing green production methods, using fermentation or novel extraction to shrink environmental footprints and lower costs. As sports medicine and plant-based food segments expand, potassium malate stands out as a steady workhorse, balancing flavor with nutrition. In the future, expect new forms and applications—possibly time-release capsules or double salts—thanks to ongoing innovation by food chemists, nutritionists, and pharmaceutical scientists invested in mineral and acid balance.

Potassium malate blends two important nutrients: potassium, an essential mineral, and malic acid, a compound found in many fruits. People often overlook these nutrients in their daily routine, but missing out on them means missing out on real health benefits. Food manufacturers mix potassium with malic acid for reasons beyond just taste or stability. The body absorbs potassium malate differently than ordinary potassium, and that difference actually matters.

Most folks recognize potassium as a salt that doctors mention during blood pressure checks. Low potassium causes cramps, weakness, and sometimes puts the heart rhythm at risk. Potassium malate delivers what the body craves, especially if meals lack green vegetables and fruits. In my own kitchen, meals rarely reach the recommended potassium intake unless I pay close attention, and research shows many adults fall short by thousands of milligrams daily.

What’s interesting: potassium in malate form seems easier on sensitive stomachs compared to potassium chloride, which is common in supplements. I once tried traditional potassium tablets and needed to stop because of discomfort. When I switched to malate, the issue disappeared. Stomach-friendly options help people stick with a supplement long-term.

Keeping potassium at healthy levels supports smooth and steady muscle contractions. This goes far beyond bodybuilders or athletes. Anyone who’s woken up to a charley horse at 2 a.m. knows the pain of low potassium. Proper levels help prevent those spasms. Potassium also works behind the scenes to keep heartbeats regular, an effect confirmed by years of clinical research. Both the American Heart Association and the CDC highlight potassium’s link to healthy blood pressure.

Malic acid doesn’t just hang around for taste. Scientists discovered that malic acid plays a vital role in the Krebs cycle, the main way our cells turn food into energy. Some research connects supplemental malic acid, combined with magnesium, to reduced muscle soreness after intense exercise. Anyone balancing active days and long work hours can relate to muscle fatigue and that drained feeling. Potassium malate works in tandem with the body’s natural energy-making process. It helps the cells pump out more usable energy, and anecdotal reports support that it reduces that heavy-legged feeling after workouts.

A few small studies and patient testimonials point toward potassium malate, often paired with magnesium, offering some relief to people living with long-term fatigue or muscle pain, especially those with conditions like fibromyalgia. Doctors don’t have all the answers, but many patients try this combo after standard approaches come up short.

Before adding any supplement, it helps to check with a healthcare professional. Not everyone benefits from high potassium. Folks with kidney trouble or people taking certain medications need to approach carefully. People interested in giving potassium malate a try should look for a product from a reputable source. Quality control and clear dosing information matter, especially since potassium can cause problems if overused.

Simple dietary tweaks work too. Adding more leafy greens, beans, squash, and even apples (rich in malic acid) supports the same nutritional goals. Potassium malate serves as a practical solution for people with gaps in their diet or higher needs because of lifestyle, work demands, or health conditions. Backed by science, confirmed through personal experience, it stands out in the world of nutritional support.

Most people first hear about potassium malate as an ingredient in electrolyte supplements or as something found mixed into some processed foods. It’s not only a food additive, though—it’s a combination of potassium, a key mineral for our heart and muscles, and malic acid, recognized for its connection to the tartness in apples. The goal with potassium malate is clear: help keep potassium levels up while supporting energy production.

Let’s talk potassium. Leg cramps, irregular heartbeat, or fatigue? Low potassium may play a part. Athletes, folks on certain medications, or those with specific medical conditions sometimes need help keeping up their intake. The official daily recommended potassium intake for most adults sits at about 4700 mg. That’s the total, no matter if it comes from a banana, a glass of orange juice, or a supplement.

On the other hand, malate comes from fruits, mainly apples. It’s part of the body’s energy cycle, turning what we eat into fuel. When these two come together, the supplement takes on a specific job—supporting cellular energy while helping to balance electrolytes.

Potassium malate supplements aren’t as common as potassium chloride, but they’re popping up more often in health food stores and online shops. Most of these capsules or powders contain somewhere between 99 mg and 200 mg of potassium per serving. The main reason for this cap is safety. The FDA puts strict limits on the potassium offered in over-the-counter supplements for a very real reason—too much can hurt the kidneys or affect the heart rhythm, especially for people with chronic conditions or who are taking certain drugs.

Supplements rarely offer more than 99 mg because high single-dose potassium can risk sudden spikes in blood potassium. Instead, these smaller doses let people top up a diet already rich in natural sources: leafy greens, potatoes, beans, avocados, and juicy fruits. Anyone considering a supplement ought to use it to fill occasional gaps, not replace a balanced plate.

As someone who’s trained for endurance events and done more than my share of sweating, I know how tempting electrolyte powders become after a long day outdoors. Years ago, I decided to try a potassium malate blend, first out of curiosity, and later to ward off nighttime cramps. The small print on the packaging stuck with me—“Not for individuals with kidney disease.” That single sentence says a lot. Potassium doesn’t leave the body fast if the kidneys aren’t working right.

Talking about changes to your supplement plan with a healthcare provider always feels like an extra step, but it keeps you safe. Dieticians or doctors check for prescription drugs or medical reasons that might change how your body handles potassium, such as blood pressure medications or diabetes.

For most people, focusing on foods brings enough potassium without trouble. Supplements like potassium malate work best as a sidekick, not a star player. Trust your taste buds and health habits to guide the way, and use packaged support only with purpose.

If you do add potassium malate to your routine, picking a reputable brand can’t be skipped. Look for products certified by groups like NSF International or USP, which test for purity and label accuracy. And always be wary of high-dose powders or pills sold without clear instructions—less is usually smarter than more where potassium is concerned.

Potassium malate often shows up in foods, supplements, and even some skincare products. On its own, potassium keeps muscles working, nerves firing, and blood pressure steady. Combine that with malic acid, which comes from apples and gives sour candy its zing, and you get a salt that delivers both taste and a chemical punch used in food processing and health supplements.

While most people treat potassium malate like any other mineral blend in their daily multi-vitamin, there are real risks, especially for those with health problems that mess with kidney function. The kidneys keep potassium in check, so anyone with chronic kidney disease or those taking water pills for heart conditions often struggles to clear extra potassium. Swap in potassium malate on top of dietary sources, and blood potassium can creep up. High potassium in the blood, or hyperkalemia, causes muscle weakness, nausea, and in serious cases, heart problems that demand a hospital visit.

Healthy folks rarely end up there by accident, but symptoms like cramps or mild stomach pain do pop up, mostly when someone downs potassium supplements on an empty stomach. There are also rare allergic responses—rashes, swelling, trouble breathing—but these aren’t typical with potassium malate specifically and rarely crop up for most people without significant allergies.

The National Institutes of Health sets the upper limit of potassium intake at around 4,700 milligrams per day for most adults, and most get nowhere near this from food alone. Potassium malate in supplements shouldn’t push anyone over this limit, but toss it on top of diets packed with bananas, potatoes, avocados, or leafy greens, and it gets easy to overshoot. Regular blood work keeps things honest, especially for people with kidney disease, diabetes, or those who take blood pressure meds called ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

Doctors almost always flag potassium supplements for patients with kidney disease, since the risk ramps up fast. For people like me who juggle blood pressure medicine, the warning comes up at every appointment. Extra potassium—regardless of the source—can throw off the careful balance that medications and diet try to keep in place. I once thought “it’s just a mineral, what’s the harm?” Years later, I’ve sat through lectures and read enough cautionary tales that I take extra potassium the way I’d handle a strong prescription drug: with respect and an eagle eye on the label.

Check every supplement label before buying, and if potassium malate sits in the list—in a sport drink, capsule, or food—think about where else potassium creeps in throughout the day. Ask the doctor or pharmacist about safe limits and call the clinic if nausea, tingling, or odd fatigue stick around. Food almost always offers a safer route since our bodies handle slow, steady intake better than one big dose.

A little knowledge helps most avoid the pitfalls. For those wrestling with health problems, it’s worth sitting down with a medical professional to map out a plan. Potassium malate falls into that zone where benefits exist, but smart, careful use wins every time.

Every time you take a sip of a flavored drink or bite into a neatly packaged snack, there's a good chance potassium malate is helping shape your experience. It doesn’t command the same attention as table salt or baking soda, but its behind-the-scenes influence is huge. In food processing, potassium malate balances tartness without leaving a sharp aftertaste. I remember the first time I tried to make homemade lemon-lime soda—no matter how much lemon I used, it was always too harsh or too sweet. Commercial drinks often get this balance right, partly because of potassium malate’s subtle touch.

Besides smoothing flavors, potassium malate helps control acidity in foods. The food industry turns to it because it's great at buffering. Take fruit-flavored yogurts, shelf-stable juices, and even some cheeses. These products benefit from a consistent, pleasant taste that doesn’t overwhelm the palate. Potassium malate is known to prevent flavors from turning too sour over time. The shelf stability it provides means less food waste, and that’s something I appreciate both as a consumer and someone who worries about sustainability.

Potassium is a key dietary mineral for muscle and nerve function. With many people skimping on fruits and vegetables, food scientists look for ways to help fill that gap. Potassium malate provides potassium in a form that the body absorbs efficiently, especially compared to some other potassium salts that can upset the stomach or taste harsh. During long study sessions in college, I reached for “fortified” snacks with added potassium—they kept muscle cramps at bay, especially during marathon sessions at the library. Having foods that multitask (like quenching your thirst and supporting your nerves) matters in a busy world.

Some research teams are looking at potassium malate for its possible role in managing kidney stone risk. Because it helps the body handle acid, potassium malate may help reduce the formation of certain kidney stones. Doctors sometimes recommend similar compounds, such as potassium citrate, to patients with kidney health concerns. Scientists are still exploring these connections, but the early evidence is promising. Policies supporting science-driven ingredient choices could help more people get health benefits from staples on grocery shelves.

Every food additive has skeptics. That’s healthy. Transparency about how potassium malate is sourced and used helps build trust. It’s produced by combining potassium compounds with malic acid, which comes from apples and other fruits. Rigorous studies have found it safe at approved levels, and regulatory agencies keep tabs on its use in foods.

More people read food labels today, and they want real answers about what they’re eating. Manufacturers should keep sharing clear information about ingredients. Policies that encourage ongoing research and open communication will likely support confidence in the safety and usefulness of potassium malate. Seeing how it improves shelf life, taste, and nutrition, it earns its place on the ingredient list for many everyday foods.

Potassium malate mixes potassium, a mineral our bodies rely on, with malic acid, something we find in apples and many fruits. Food producers often use it to adjust acidity and boost flavors. Some athletes and people after mineral supplements ask if potassium malate fits into their daily routines. I had questions, too, after seeing it listed in some electrolyte powders.

Anything going into our bodies day after day calls for real scrutiny. My experience tells me: the more obscure the additive, the more careful I get. Still, potassium and malic acid themselves both have a lengthy track record in human health. The World Health Organization says potassium compounds, used reasonably, rarely spur trouble. Malic acid has been in food for generations without raising red flags.

One concern: overdoing potassium can stress the kidneys, especially in people with kidney troubles. Medical literature confirms too much potassium leads to hyperkalemia, an electrolyte imbalance that may be life-threatening in rare cases. If kidneys already work at half-speed, taking added potassium without medical advice risks trouble. Malic acid seems less worrisome — studies show people tolerate it well, even over long periods.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recognizes malic acid and potassium forms as “Generally Recognized as Safe” when used as expected in foods. I checked into regulatory limits — they come with the expectation people won’t mainline the stuff. Natural sources like fruits rarely cause overdose. Problems might start if you use huge supplemental doses or already eat a potassium-rich diet (bananas, spinach, avocados, nuts). Most folks eating a typical mix of foods don’t run into issues.

People with healthy kidneys who don’t exceed typical serving sizes — especially from food sources — usually find no problems with potassium malate. During a stint using powdered electrolytes for marathon training, I watched for muscle cramps, stomach aches, or heart palpitations and found no ill effects when sticking to suggested amounts. Peers with kidney disease, though, told me their doctors warned against taking any extra potassium.

Not all supplements label their exact potassium content. Too much can add up quickly if combined with other pills or processed foods. Some folks with heart conditions or on certain blood pressure medications (like ACE inhibitors or potassium-sparing diuretics) quietly build up potassium. Symptoms like tingling arms, muscle weakness, or irregular heartbeat demand prompt medical review, since they hint at imbalance.

Most healthy adults, after researching and using potassium malate within recommended limits, rarely report trouble. Parents, older adults, and athletes may want extra guidance if they take more than the minor amounts in food. A diet filled with whole foods brings plenty of potassium and malic acid in ways nature intended. Whenever something feels off, or health changes, talking with a healthcare provider helps keep things safe and personal.

Safe long-term use isn’t about fear — it’s about moderation, honest labels, and real-world medical context. Supplements can fit in, but food still gives us the best mix of nutrients and safety.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium 2-hydroxybutanedioate |

| Other names |

Potassium salt of malic acid Dipotassium malate Potassium(2S)-2-hydroxybutanedioate |

| Pronunciation | /pəˈtæsiəm ˈmæleɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 877-24-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1904606 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:63315 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201651 |

| ChemSpider | 174196 |

| DrugBank | DB14573 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.032.604 |

| EC Number | E351 |

| Gmelin Reference | 86792 |

| KEGG | C18634 |

| MeSH | D017601 |

| PubChem CID | 23667630 |

| RTECS number | OW7525000 |

| UNII | 7X5R3C50VN |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | K2C4H4O5 |

| Molar mass | 188.22 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.01 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -4.32 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.40 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 9.62 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.463 |

| Dipole moment | 2.51 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 286.4 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1496.4 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12BA14 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3,200 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Potassium Malate: "LD50 oral, rat: 1600 mg/kg |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL for Potassium Malate: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2000 mg per day |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Malic acid Potassium citrate Potassium fumarate Sodium malate Calcium malate |