Zinc compounds trace their roots back to ancient medicine and metallurgy. Centuries ago, healers used zinc ointments for wounds, appreciating zinc's role long before anyone tracked its chemical makeup. As scientific understanding grew through the 19th and 20th centuries, zinc joined the world of commercial chemistry. In the late twentieth century, efforts to fill nutritional gaps and improve oral care zeroed in on zinc citrate dihydrate—one of the more bioavailable forms. The journey from ancient pharmacies to modern factories touches on both curiosity and industry standards. Over the years, refining production meant improving purity and handling, often driven by increased demand from both supplement users and toothpaste brands.

Zinc citrate dihydrate emerges as a white to nearly white powder, mainly used as a dietary zinc supplement and an antimicrobial agent in oral care. This chemical doesn’t just show up in one arena—pharmaceuticals, nutritional products, and personal care lines regularly call on it. Its taste isn’t offensive, and it dissolves in water at a rate that suits most supplement manufacturing. Chemically, this substance merges the essential mineral zinc with citric acid, giving it both stability and improved absorption when compared to some older zinc salts.

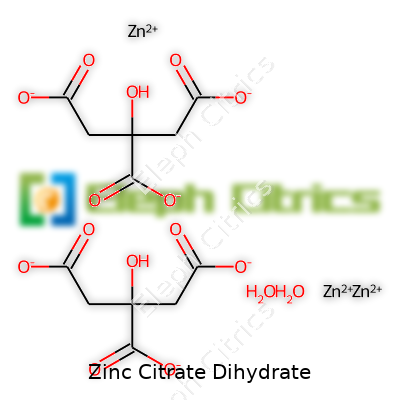

Zinc citrate dihydrate often appears as a fine, crystalline material. Unlike zinc oxide, which tends to clump and resist water, this compound spreads out smoothly and dissolves at room temperature, easing its use in both tablets and dental products. The molecule pairs zinc ions with citrate and binds two water molecules. It carries a molecular weight close to 389.8 g/mol and a melting point between 100–110°C where it gives off water before breaking down at higher heat. The powder has a neutral to slightly acidic pH, making it less likely to irritate in nutrition or skin contact compared to stronger mineral acids or bases.

For supplement and food uses, regulations in North America, Europe, and Asia shape the acceptable purity levels, heavy metal content, and labeling instructions. Labels on bulk containers and finished products must include net weight, batch code, storage guidance (cool, dry, protected from light), ingredient lists, and nutrition information. Users check for a minimum 97–99% assay (content by zinc), with limits on contaminants such as lead, cadmium, and arsenic well below international safety thresholds. Authenticity and traceability take priority for manufacturers, who now often match supply chains to published monographs from references such as USP, EP, or national pharmacopeias.

Most factories start with zinc oxide or zinc carbonate, then introduce citric acid under controlled temperature and moisture. Reacting zinc oxide with citric acid in water triggers a process where zinc ions bind to citrates and crystallize out as the hydrated salt. The resulting slurry gets filtered, washed, and dried at low temperatures to preserve the two water molecules. The finished material heads through sieving to ensure consistency. Some labs focus on reducing batch-to-batch variability, using automated reactors and real-time monitoring systems. Each tweak in temperature or acid ratio shifts yield, purity, and hydration level, so tight controls often mean fewer waste streams and a more eco-friendly outcome.

Beyond daily use, investigators occasionally alter zinc citrate dihydrate to fit specific industrial demands. Heating strips the water, leaving a dry anhydrous form. In certain settings, changing the pH or adding chelating agents produces specialized citrate complexes. Scientists track these changes through spectroscopy or chromatography, ensuring no unwanted byproducts slip through. Some researchers pursue nano-scale modifications, intending to boost bioavailability in high-performance supplements, though most bulk manufacturers keep to the hydrated standard for stability and safety.

Products in global markets recognize zinc citrate dihydrate under several names: zinc citrate tribasic dihydrate, trizinc dicitrate dihydrate, and simply zinc citrate. On product labels, it may appear as “zinc (as citrate dihydrate),” keeping compliance with dietary supplement guidelines. Chemistry databases and regulatory filings sometimes list its CAS number—an industry device to cut confusion in sourcing. These names all describe roughly the same molecular entity, though grades and hydration levels differ.

Production and handling of zinc citrate dihydrate require vigilance to protect staff and end-users. Fine powder means airborne dust can irritate lungs or eyes, so operators wear masks, gloves, and sometimes goggles. Workstations rely on extraction systems, and routine cleaning stops buildup. On the consumer side, excess zinc from any source risks nausea or digestive upsets, so supplement makers warn against high dosing. Certification bodies in the supplement and food sectors carry out third-party audits, confirmation testing, and scrutiny of supply chains, helping spot contamination or dilution. Each country enforces its own workplace standards—OSHA in the US, REACH in Europe, and similar laws around the globe—covering storage, clean-up of spills, fire hazards, and long-term exposure.

Zinc citrate dihydrate stands out in oral care, especially toothpaste and mouthwash, because it cuts down on plaque and slows tartar build-up. Dental researchers found zinc’s antibacterial traits help with bad breath and gum sensitivity, so brands include it across product tiers. Supplement makers blend it into capsules, powders, and lozenges, leaning on the body’s need for regular zinc intake for immune and enzyme support. In animal nutrition, this form avoids the metallic taste of zinc sulfate, prompting better food intake in livestock. In food fortification, it brings efficient zinc delivery without clouding liquids or altering the flavor profile. Pharmacies sell it alone or combine it with vitamins and minerals, answering the growing interest in filling dietary gaps, especially in older adults.

Academic teams spend time comparing zinc citrate dihydrate to other zinc salts, mapping how the body absorbs, retains, and uses each. In recent years, research highlighted the better tolerability of citrate over sulfate or gluconate, especially in sensitive groups. Biochemistry labs look into micron-sized vs. nano-sized forms, curious whether smaller particles reach tissues faster or carry fewer side effects. Dental schools work with manufacturers, testing tailored blends for more lasting oral health results. The medical community builds databases tracking usage patterns and consumer feedback, flagging cases where more or less zinc could benefit public health.

Concerns about toxicity typically relate to overdosing or prolonged use rather than moderate, daily intake. Scientists measure how much zinc citrate dihydrate the body absorbs, excretes, and stores. Acute studies with animals or cell lines reveal a fairly wide safety margin, provided supplement users or manufacturers respect established dosing limits—usually around 8–11 mg zinc per day for adults. Chronic exposure beyond suggested upper limits can bring copper deficiency or gastrointestinal distress. Risk assessments from regulatory agencies shape modern guidance, and clinical case reports anchor real-world risk in clear, evidence-based numbers. Health professionals flag at-risk groups—such as children, pregnant people, and those with kidney problems—for special caution.

Zinc citrate dihydrate will likely see broader use as nutritionists, doctors, and regulators emphasize preventive care. Innovations in personalized nutrition could tailor zinc intake to personal metabolism or disease risks. Ingredient suppliers invest in cleaner synthesis, better particle control, and new delivery forms—think chewable gels or slow-release tablets. Public interest in immunity, bone health, and oral hygiene all suggest expanding demand. As researchers publish bigger and better clinical studies, clearer evidence around benefits and safe range can inform smarter product design. Technology from pharmaceutical manufacturing cascades into food and supplement lines, letting more people get enough zinc with less cost and lower environmental impact. The story of zinc citrate dihydrate, then, goes on—its roots in history fueling new possibilities in global public health and daily life.

Nearly every time I stroll down the aisle of a pharmacy, I spot supplements and toothpaste touting "zinc" as a key ingredient. Not all forms of zinc are equal, though. Zinc citrate dihydrate brings something special to the table, and that's not just marketing spin. This compound often pops up in dietary supplements and dental care products, specifically toothpaste and mouthwash. Kids and adults alike benefit from its use, though for different reasons.

Getting sick less often isn’t the only perk folks chase with zinc citrate. The body needs zinc to function; we're talking over 300 enzymes and plenty of daily metabolic work count on it. Zinc citrate dihydrate steps in as an easy-to-absorb source, especially for people whose diets skimp on zinc-rich foods like beef, lentils, or pumpkin seeds. One survey from the National Institutes of Health pointed out that around 12% of Americans might not get enough zinc from food alone.

Doctors recommend zinc for immune support. Studies published by the Mayo Clinic and others have shown that regular zinc intake can shorten the duration of common colds. Athletes sometimes reach for supplements after intense training, since strenuous exercise may lower zinc. Even teenagers and those dealing with acne turn to it, since it plays a role in healthy skin repair.

Toothpaste and mouthwash companies put zinc citrate dihydrate in formulas because it handles more than breath freshness. Research shows that zinc helps reduce plaque buildup and might even fight gingivitis, the inflammation that makes gums bleed. European regulations around oral care lean into zinc’s safety profile, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers it safe as a food additive and supplement when taken at suggested doses.

People who struggle with bad breath often end up reading the small print and find zinc citrate listed among the ingredients. It’s no accident. By reducing the volatile sulfur compounds that create odors, this type of zinc cuts down on embarrassment and social worry, without the heavy medicinal taste some mouthwashes carry.

Zinc is good, but more doesn’t always mean better. Adult men only need around 11 milligrams a day, while women need 8 milligrams, according to the National Institutes of Health. Taking too much, especially over long periods, can cause nausea or even knock down copper levels in the body. Labels on supplements spell out serving sizes, but it never hurts to check with a healthcare provider before adding new pills or powders, especially for kids, seniors, or those on medication.

Most people who eat a varied diet get enough zinc, but special cases exist. Vegetarians, pregnant women, and certain older adults might find themselves on the low end. Zinc citrate dihydrate shows up in chewable supplements, lozenges, and toothpastes because the body soaks it up more easily than some other forms like zinc oxide.

Reliable brands pay attention to sourcing and quality testing. When picking a zinc product, looking for certificates of analysis, professional endorsements, and clear dosing instructions makes a real difference. This helps avoid both mislabeled products and unnecessary fillers.

Research keeps evolving. The need for trace minerals like zinc isn’t about hype, but meeting what bodies actually miss. By focusing on trusted products, reasonable dosing, and balanced diets, people can pull real benefits from zinc citrate dihydrate without the worry of going overboard or falling for empty promises.

Zinc plays a part in keeping immune cells working right, wound healing, and even the way our bodies process food. Every time flu season swings around, shelves fill up with zinc supplements. People take it hoping to dodge sniffles, boost recovery, or just cover nutritional gaps. Getting enough zinc is key, but that doesn’t mean more is better. Taking too much can cause as many problems as not getting enough.

Health agencies and nutritionists agree on a range instead of a one-size-fits-all amount. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for zinc is 11 mg a day for grown men and 8 mg a day for women. Pregnant and breastfeeding women need a bit more, sitting at 11 mg to 12 mg daily. These numbers usually refer to total zinc intake from diet plus supplements. Zinc citrate dihydrate contains zinc in a form that the body absorbs well, so it counts toward the daily total just like zinc from chicken or lentils.

Supplements come with their own set of instructions, but most off-the-shelf zinc citrate tablets hand out anywhere from 15 mg to 50 mg per serving. That higher range doesn’t mean everyone needs to reach for these doses. The Food and Nutrition Board warns against regular intake above 40 mg daily from all sources for adults, since this could lead to side effects like nausea or messing with copper absorption. Speaking from experience, I learned the hard way after taking too much zinc for a winter cold and wound up with an upset stomach.

A doctor or dietitian will treat zinc needs differently for those with certain health conditions. People with digestive issues like Crohn’s disease or folks who eat a plant-based diet may need more since their bodies snag less zinc from food. On the flip side, kids and teens shouldn’t just copy adult dosage. Children between 1 to 3 years need only about 3 mg a day, scaling up as they grow.

For short-term use—say, during the early days of a cold—a temporary bump in zinc, under medical guidance, doesn’t usually cause trouble. There are studies showing that lozenges with 15 mg to 25 mg zinc taken several times a day at the start of a cold may shorten symptoms, but these protocols should not stretch for weeks. Long-term high dosing puts nerves, digestion, and mineral balance at risk.

Labels tell only part of the story. The real answer comes down to understanding your own diet, checking with a healthcare provider, and paying attention to your body. Anyone taking other medicines should ask about interactions, especially those using antibiotics like tetracyclines or medications for rheumatoid arthritis, since zinc can lower how much medicine the body absorbs.

Zinc from food rarely poses a problem, but piling on pills can. It’s smart to treat supplements as just that—a way to fill small gaps, not replace a varied diet. I always remind friends not to start any mega-dosing just because a supplement is easy to buy or trending online. Instead, aim for balanced meals, consider your real dietary intake, and treat labels as guidelines, not guarantees of better health.

Zinc often pops up in lists of essential nutrients, and most adults understand why our bodies need a steady supply. Whether for a healthy immune system or to help wounds heal up, this mineral pulls more than its weight. Food isn’t always enough to meet higher needs, though, and supplements like zinc citrate dihydrate enter the conversation. The “dihydrate” part just means it contains water molecules along with the zinc, which helps it dissolve and absorb better in the gut. But, as with anything you swallow hoping to get health benefits, side effects deserve more than fine print treatment.

Start with the most commonly reported issue: gut trouble. People sometimes “meet” nausea, a queasy stomach, heartburn, or diarrhea after adding zinc citrate dihydrate to their routine. I’ve noticed this myself, especially when I’ve tried taking zinc on an empty stomach. Doctors often suggest pairing it with food for a good reason. The body handles nutrients best with a meal, and tossing back a tablet without a buffer proves rough for some folks.

Next, too much of a good thing turns sour. Taking high doses of zinc citrate can lead to copper deficiency, a real problem since copper sustains red blood cells and keeps nerves healthy. The U.S. National Institutes of Health flags 40 mg a day (for adults) as a safe upper limit from both food and supplements combined. I’ve seen people go overboard chasing “immunity hacks” online, then wonder about strange tiredness, frequent sickness, or even tingling in their limbs. It’s a classic case of “more does not always equal better.”

Some groups play with higher stakes. Kids and pregnant women should only use supplements on a doctor’s recommendation because dosing mistakes scalp health quickly in developing bodies. Those with kidney problems need close supervision, since their bodies can’t clear minerals as efficiently, raising the risk of complications.

One thing many folks miss: zinc can mess with certain medications. Antibiotics, for example, absorb poorly if you’ve just swallowed zinc. In my own household, a family member with thyroid disease learned through trial and error that timing matters—thyroid pills and zinc too close together, and the medication doesn’t work as expected. Pharmacists can run through the best ways to avoid this headache.

Label reading helps more than wishful thinking. Supplements often come bundled with other vitamins or minerals, and people lose track of their total daily zinc intake. Mixing a multivitamin and separate zinc bottle often tips someone over the safe limit. Speaking openly with a healthcare provider about everything you take can spot these overlaps before they become a problem.

Research at places like Harvard and the Mayo Clinic keeps up with supplement trends. They agree that moderate use, especially short-term, provides benefits to those who truly need extra zinc, like some vegetarians or older adults with absorption issues. Still, the best source of zinc comes from food—meat, shellfish, beans, and seeds. Supplements fill gaps, but they can’t replace a balanced meal.

Long-term health rests on honest conversations and reading past the marketing lingo. Zinc citrate dihydrate helps many people, but ignoring side effects or mixing bottles without a plan causes more trouble than most realize. Listening to your body, trusting science-backed advice, and keeping healthcare providers in the loop turns good intentions into real health benefits, not just another bathroom emergency.

You see zinc citrate dihydrate listed on supplement bottles in the vitamin aisle, in kids’ chewables, and often in oral care products. It’s not some obscure chemical. It’s just a form of zinc bound to citrate, with a little water for stability. The body needs zinc for everything from wound healing to keeping the immune system on its toes. But knowing something is necessary doesn’t always mean more is better, or that it’s smart to take it every day for years.

Most people know zinc as a cold-buster or a mineral you want more of when flu season hits. Doctors point out that zinc supports enzymes, DNA repair, and the sense of taste. The low end of the safe range starts around 8 mg per day for women and 11 mg for men. Getting zinc from foods — beans, nuts, whole grains, dairy, meat — usually covers daily needs.

Supplements deliver zinc fast and guarantee a fixed dose, but swallowing too much over time can sabotage the body’s fine balance. Even doses a little above the daily recommended value can sneak up and reduce copper absorption, weaken immunity, or trigger side effects like nausea. This matters because over-the-counter supplements rarely come with a clear, science-backed warning about how much is truly “too much” for someone taking them every day for months or years.

Decades of research generally show zinc citrate dihydrate is effective and absorbs well in the gut — maybe even a tick above zinc gluconate or sulfate. Multiple studies and professional health organizations confirm the safety and usefulness of zinc supplements, including citrate dihydrate, but only in the right range. Too much, for too long, increases risk for issues like lower HDL (the “good” cholesterol), anemia, or even weakened immunity.

Manufacturers keep zinc levels below toxic limits; the U.S. National Institutes of Health mark the upper intake level for adults around 40 mg per day from all sources. That’s not a dare — just a safety fence. Recent reviews suggest no evidence of toxicity when people take recommended doses for months, but bumps in the road appear with high-dose, long-term use. One study found regular use above 50 mg per day for more than a couple of months linked to drops in copper and immune trouble.

Labels help, but personal factors matter. Age, health problems, and what you already eat influence how much extra zinc you actually need. If you’re considering taking zinc citrate dihydrate as a supplement for more than just a cold or a week or two, it's smart to check with a healthcare provider. Testing for zinc or copper levels usually isn’t routine, but a doctor can flag possible signs if the balance tips — fatigue, poor wound healing, or taste changes.

People often forget to count dietary zinc and multivitamins along with single-mineral supplements. Adding up everything you consume, even the zinc in fortified cereals, paints a truer picture and avoids accidental overload. Using one reputable product, following the label or a doctor’s guidance, and not doubling up on different zinc supplements helps avoid chronic excess.

Zinc citrate dihydrate can offer real benefits for physical health, especially if tests reveal a deficiency or recovery from illness needs a boost. But long-term, mindless use stacks up possible problems, not extra protection. Like most things in health, moderation and real information win out over guesswork.

Zinc doesn’t get as much attention as some other nutrients, but it powers hundreds of processes in the body. Zinc citrate dihydrate delivers this essential mineral in a way the gut can easily absorb. Many people look to supplements because soil depletion, aging, or certain diets make it tough to rely on food alone for their zinc.

Taking a bunch of pills at once tends to get messy. I’ve seen more than a few folks at the pharmacy counter with a long list of supplements and prescription bottles, maybe a multivitamin, some iron, a calcium chew, maybe magnesium for sleep. Then someone asks, “I just picked up this zinc citrate — can I add it too?”

It’s a fair question. Zinc often works side by side with other nutrients. Still, things can go sideways without care, especially with minerals like iron or copper. Zinc and copper compete for absorption, so when someone loads up on zinc without enough copper, problems like anemia or nerve changes can creep up more quickly than they’d expect. In fact, the National Institutes of Health warns about this risk for people who use high-dose zinc supplements for longer stretches.

Iron joins the tug-of-war, too. Zinc can slow iron absorption and vice versa. Folks with iron-deficiency anemia often reach for both minerals but overlook that they sometimes work against each other when taken together. Same goes for calcium. Swallowing zinc and calcium at the same meal can cut back how much your body takes in.

Some medicines don’t love sharing space with zinc. Antibiotics like tetracycline and quinolones get blocked by minerals such as zinc, so much less of the drug makes it to the bloodstream. There’s good data showing zinc cuts how well these medications work, so many doctors and pharmacists warn patients to space them out by at least two hours. Diuretics — “water pills” like hydrochlorothiazide — speed up zinc loss in urine, and people who use them daily wind up more likely to get zinc deficient over time.

People taking drugs for autoimmune conditions, rheumatoid arthritis, or high blood pressure should also loop their doctor in if they’re starting a new supplement. The reality is, supplement-drug interactions show up more often than most think. Nutrition can’t fix everything, but missing or doubling up on minerals does set the stage for real trouble.

No one wants to shuffle around a bunch of pill bottles morning and night, or worry every dose will cause a problem. Building a supplement schedule sounds tedious, but it’s often the difference between problems and progress. I usually tell people splitting up minerals — for example, zinc at lunch, iron with breakfast, calcium at dinner — helps the body make the most out of each.

Most importantly, talk it through with someone who really understands your medical history. Pharmacists and advanced practice nurses look for possible interactions every day, and a quick review before stacking supplements or starting a new prescription can avoid headaches, literally and figuratively. Blood work sometimes helps guide these choices, so don’t be shy about asking your provider to monitor mineral levels.

The world of supplements offers plenty of benefit when handled with attention and a little expert backup. Zinc citrate dihydrate plays a supporting role, not the entire story. Mixing wisely brings the best results.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | zinc di(2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate) dihydrate |

| Other names |

Zinc citrate Zinc(II) citrate dihydrate Citrate de zinc dihydraté Trizinc dicitrate dihydrate |

| Pronunciation | /ˌzɪŋk ˈsɪtrət daɪˈhaɪdreɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 5990-32-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 615872 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:86373 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201647 |

| ChemSpider | 8359181 |

| DrugBank | DB14545 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 01a0c66e-7772-41b4-9767-9982dfcdc307 |

| EC Number | 200-788-1 |

| Gmelin Reference | 77581239 |

| KEGG | C05925 |

| MeSH | D017693 |

| PubChem CID | 159393 |

| RTECS number | ZHM7530000 |

| UNII | SDT16H6G97 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | Zinc Citrate Dihydrate CompTox Dashboard ID: "DTXSID10897963 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Zn₃(C₆H₅O₇)₂·2H₂O |

| Molar mass | 574.35 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to almost white powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | DENSITY: 2.3 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble in water |

| log P | -1.7 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.0001 hPa at 20°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.7 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.49 |

| Dipole moment | 7.09 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 427.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1817.1 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CB05 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302, H315, H319 |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-1 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 1126 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 3500 mg/kg (Rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | GRN000287 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 60 mg/day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Zinc acetate Zinc gluconate Zinc sulfate Magnesium citrate Calcium citrate |