Zinc lactate hasn’t always been front-and-center in the world of nutritional supplements and specialty chemicals. In the early days, folks relied on dietary zinc alone from nuts, meats, and grains. By the mid-twentieth century, labs grew more interested in pure, bioavailable forms of minerals, especially as researchers linked zinc to everything from immune health to skin repair. Manufacturers started searching for salts of zinc that the human body actually takes up well. Lactic acid, a byproduct of fermentation—think yogurt and sour milk—showed promise as a partner. Marrying lactic acid and zinc gave chemists a compound that dissolves and absorbs reliably. Pretty soon, this landed on ingredient lists for supplements and fortification, especially where nutritional deficiencies popped up. From pill bottles to toothpaste, zinc lactate crept in, riding on claims of better health and stronger bodies.

At its core, zinc lactate brings together organic and inorganic chemistry: zinc, a heavy-hitter trace element, bonded to the lactate ion from lactic acid. The compound typically appears as a white, tasteless powder. Beyond the supplement industry, it pops up in oral hygiene products, food additives, and even industrial applications like plating and leather processing. Its value comes from combining zinc’s health punch with a molecule the body already recognizes. This makes zinc lactate a key choice wherever enhanced uptake matters. In my work with food scientists, few other zinc supplements see as much use—there’s just less stomach upset, and absorption rates remain high. Compared to zinc oxide or gluconate, lactate wins on tolerability.

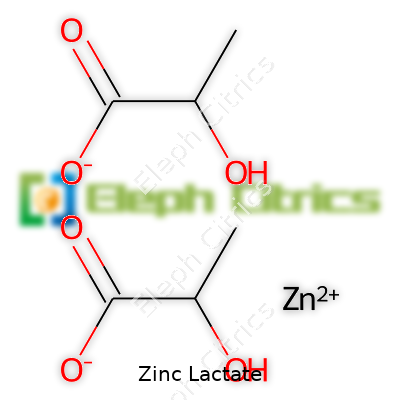

Zinc lactate appears as a white crystalline powder. Its chemical formula is C6H10O6Zn. It dissolves easily in water, meaning it disperses quickly in solution or the body. Melting points hover around 210°C, but practical uses don’t see such extremes. It leaves a neutral taste, which helps when mixing it into foods or rinses. In fact, zinc lactate’s solubility and low taste profile have made it a go-to in oral care products, where bitterness and grittiness turn users away. Its pH tends to sit just on the acidic side when in solution, which plays a role in product stability. From a technical angle, it’s one of the few zinc salts that doesn’t clump or degrade under regular storage, so shelf life presents little worry.

Manufacturers typically aim for a zinc content near 22% by weight in their zinc lactate powder. Purity often hits 98% or better, and color should stay snow white. Heavy metal impurities stay well below regulatory cutoffs—well under 10 ppm for lead, for example. Brands selling true food or pharmaceutical grade product run batch testing to confirm specs. Labels need to show zinc content, chemical name, and manufacturer details. Many supplement regulations call for a warning that pregnant women or kids under six consult doctors before use, since mineral supplements sometimes interact with medications. Any product hitting the US or European market posts these numbers right on the side, handy during audits. In my experience, rigorous labeling beats lawsuits and keeps customers coming back.

Making zinc lactate looks simple on paper: react lactic acid with a zinc salt, usually zinc oxide or zinc carbonate, in water. The lactic acid dissolves the zinc compound, which then forms a soluble salt—the zinc lactate. Add in a purification step to remove excess reactants, followed by filtration. The resulting solution gets concentrated, crystallized, and dried. Quality control tests the batch for purity and contamination. Some companies run this process at room temperature to keep costs down, while others add gentle heat for speed. Factories handle large stainless-steel vessels, safety monitoring, and careful waste disposal, since the acids and zinc powders can cause burns or respiratory issues in untrained hands.

Chemists have tinkered with zinc lactate’s basic formula to suit different needs. Regular zinc lactate is neutral in charge, but adding extra lactic acid turns it more acidic, changing how it dissolves in water or interacts with other ingredients. In industrial use, some processes involve reacting zinc lactate with alkaline agents to buffer it or pair it with other chelators for stronger bioavailability. Lab experiments sometimes combine it with amino acids or other weak acids, hunting for compounds that might outperform the original in supplements or even therapies. There’s also interest in pairing zinc lactate with antioxidants or flavor maskers for functional foods, making it even more versatile in consumer brands.

On paperwork or in catalogs, zinc lactate shows up under several names. “Zinc(II) lactate,” “lactic acid zinc salt,” and “E327” (its food code) all mark the same substance. Some suppliers slap on proprietary product names—LactoZinc, ZLa, or ZinLac—usually for branding purposes. In pharmaceutical registries, it can appear as “zinc lactas” or “zinc bis(lactate)”. Packaging might call out “USP grade” or “FCC grade” to underscore quality standards. Knowing these synonyms smooths the ordering process, especially in global supply chains where local names sometimes differ.

Safety always matters, and with zinc lactate, it starts with secure storage: cool, dry spaces, away from acids and oxidizers. Workers handling bulk powder wear protective masks, goggles, and gloves. Eyes sting and lungs smart if exposed to airborne dust, and chronic overuse—think megadosing—brings risks of zinc toxicity: nausea, vomiting, headaches, and interference with copper absorption. Regulatory standards in the US, EU, and Asia cap daily supplement limits, and companies track every batch from receipt to sale as part of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) programs. Quality systems like ISO 22000 and GMP keep production lines clean and paperwork in order. On top of that, FDA and EFSA monitor health claims and require incident reporting for adverse effects. I’ve seen smart brands invest in clear instructions and regular audits, which helps avoid product recalls and builds trust.

Most consumers run into zinc lactate in daily multivitamins, throat lozenges, or toothpaste. Dentists like its ability to cut halitosis and support gum health. In food, it boosts zinc levels in breads, cereals, beverages, and dairy, catching deficiencies before they start. Chefs rarely taste a difference, thanks to the compound’s benign flavor. On the industrial side, zinc lactate finds work as a mordant in leather tanning, a stabilizer in PVC, and sometimes as a catalyst. Researchers test new uses in animal nutrition, skincare products, and plant micronutrients. I’ve consulted with food technologists who praise its ability to blend with liquids while meeting health regulations—a rare combo. Though other zinc compounds exist, few match this one’s track record for overall compatibility.

Scientists keep digging into zinc lactate, chasing new angles for nutrition and therapy. Recent studies in bioavailability point to faster zinc uptake from the lactate compound compared to gluconate or sulfate. Clinical trials probe its impact on colds, wound healing, and even cognitive function. Universities team up with supplement firms, evaluating how different production methods affect particle size and gut absorption. Formulators tweak combinations with vitamins, looking for products that address specific populations: seniors, children, pregnant women. Published work appears in journals like the Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, and the findings push changes in food fortification policies. As evidence grows, so do patents and product launches. The industry shows plenty of room to innovate, especially in delivery forms: gummies, liquids, fast-melts, or transdermal patches.

Toxicologists don’t take zinc lightly. Too much, from any source, can mute copper uptake and wreck immune balance. Zinc lactate isn’t exempt. Animal studies run high-dose protocols and watch for damage to gut tissue, kidneys, and liver. So far, results suggest that the compound delivers zinc safely when kept within recommended ranges. Chronic overdosing, especially in isolated supplements, poses risks: vomiting, diarrhea, and eventually nerve issues. Regulators in the US and Europe have set upper tolerable intake levels—usually maxing out around 40 mg elemental zinc a day for adults. In the lab, cell-culture work points to low direct toxicity in normal use. My experience says that label accuracy and consumer education make all the difference; overdoses almost always trace back to poorly regulated products or off-label use.

Looking forward, zinc lactate holds strong. More people seek convenient ways to address trace nutrient gaps, especially in developing regions where diets fall short. Technical teams zero in on new delivery forms—think dissolvable strips, beverages, or medical foods. Environmental concerns push manufacturers to greener production methods, with renewable lactic acid or closed-loop systems gaining steam. Public health advocates eye zinc fortification as a way to address child development and immune challenges in low-resource communities. Synthetic biology might even yield new strains of bacteria to ferment lactic acid in-situ, dropping costs and boosting sustainability. Research may unlock therapeutic uses for specific medical conditions, such as metabolic syndromes or inflammatory diseases, based on zinc’s unique biological actions. With better data, clearer regulation, and ongoing demand, zinc lactate looks set to remain a household name well into the next generation.

Zinc ranks up there with nutrients that keep the human body running right. It's tough to talk about immune function or healthy skin without touching on zinc. Beyond that, zinc has a hand in DNA synthesis, cell division, wound healing, and keeping our senses of taste and smell sharp.

Take a supermarket stroll and check out those ingredient lists — zinc shows up in all sorts of forms. Zinc lactate, in particular, doesn't get as much attention as, say, zinc oxide or zinc gluconate, yet it pops up all over health and nutrition products for good reason.

What exactly do people use zinc lactate for? Food industry pros lean on it for its high solubility and mild flavor. Multivitamins and dietary supplements that need a zinc boost will often tap zinc lactate. You get a form that dissolves easily, so the body can actually use that zinc.

Toothpaste manufacturers favor it, too. Zinc lactate steps up as a proven warrior against oral bacteria. The compound helps combat bad breath and supports general gum health. The European Union gives it a green light as a food additive, so regulatory agencies see it as safe in recommended doses.

Zinc offers a double whammy: nutrition plus preservation. Food producers sometimes use zinc lactate to fortify everything from breakfast bars to baby food. A 2020 study in the Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology highlighted zinc’s connection with immune system defense, making fortified foods a pretty smart move during flu season or times of increased risk, like a pandemic.

Some beverage makers use zinc lactate to deliver essential minerals without the metallic aftertaste other zinc sources can leave behind. Dairy, plant-based alternatives, even sports drinks benefit from a mineral addition that doesn’t ruin the drinking experience.

Plenty of people fall short on zinc. Vegetarian diets, digestive disorders, and certain medications can set folks up for a deficiency. That leads to more than just feeling off — stunted growth in kids, slow healing, weakened immunity. Making zinc easy to absorb stands as a real health priority.

Still, overdosing on zinc brings its own risks — nausea, stomach cramps, and issues with copper absorption. The answer doesn’t lie in dumping zinc lactate into everything. Striking a balance matters. Educating consumers about recommended dietary allowances and giving clear information on supplement labels could help keep zinc where it belongs: improving health, not causing new problems.

People want to do right by their bodies, but the nutrition landscape can be confusing. Zinc lactate gives scientists and manufacturers a way to deliver this nutrient in a stable, easy-to-absorb package. Governments and health professionals have a role to play, too, by making sure the message about proper intake hits home.

Adding more unprocessed foods rich in zinc — beans, nuts, whole grains, meats — makes sense for most. For those with absorption issues or limited dietary choices, zinc-lactate-fortified foods and supplements serve as useful backstops. It’s about making sure everyone has the tools they need to fill those nutritional gaps.

Zinc lactate shows up in everything from dietary supplements to toothpaste. It’s a compound formed by mixing zinc, which supports a lot of your basic biology, with lactic acid, which the body produces when muscles work hard. It shows up on labels because it dissolves pretty well in water and tends to play nice with other ingredients.

Zinc isn’t one of those trace minerals that companies just toss in for marketing. The body needs zinc to heal wounds, keep your immune system humming, and help cells grow. In my own kitchen, you’ll find multivitamins with zinc, not because I’m worried about “wellness trends” but because my diet sometimes falls short of “nutrition poster” perfect. Manufacturers like zinc lactate because it blends easier than some other zinc salts and doesn’t leave a strong metallic taste. My experience suggests most people don’t notice it’s there.

The first thing that matters: does it actually hurt anybody? Food and pharmaceutical safety agencies, like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, have looked at zinc lactate. They’ve put it on the “generally recognized as safe,” or GRAS, list when used in normal amounts. That doesn’t mean you want to go eating spoonfuls, any more than you’d chug a bottle of soy sauce.

Too much zinc, no matter the form, can throw things off. I’ve seen folks pop zinc tabs every time they get the sniffles. High doses can mess with your copper levels, sometimes causing problems that stick around. Typical zinc supplement doses land around 15–30 mg per day for adults, which research supports as both safe and helpful for most healthy people. Trouble appears with regular high doses above 40 mg per day—nausea, cramps, and even harming your immune system more than it helps.

Once you eat or drink zinc lactate, your stomach acid goes to work. The zinc splits off and the body uses it just like zinc from other foods, such as beef, beans, or sunflower seeds. The leftover lactate isn’t special—it’s the same stuff that circulates in your blood after a jog or workout. I’ve never seen evidence showing that zinc lactate is processed in a way that makes it riskier than other zinc types, though if your kidneys struggle or you already take giant doses from other sources, you should talk to your doctor.

People sometimes worry about hidden dangers in food additives. In my life and work, I’ve found that problems pop up much more from over-supplementing or not reading labels than from the actual ingredient itself. Accidents happen when people stack multiple fortified products and end up above safe limits. It’s smart to add up everything: your multivitamin, your sports drink, even some kinds of mouthwash.

Getting enough zinc still makes a real difference for energy, skin, and immunity. If you want to bump up your zinc, consider food first—meats, nuts, and seeds pack plenty. Supplements fit best for folks with a known deficiency, vegetarians, vegans, or people with health challenges that make it hard to absorb minerals properly. Safe practice means checking supplement doses, not doubling up on products, and having a chat with your healthcare provider if you take meds or manage any chronic illness.

Zinc lactate carries about the same risk as other supplement forms, as long as you keep intake sensible. In my experience, understanding how much you’re really getting each day does more to protect health than obsessing over whether your zinc came from lactate, gluconate, or sulfate.

Zinc catches more attention in supplement aisles these days, especially for immune health. Plenty of people hear good things about zinc, pick up a bottle at the pharmacy, and hope it smooths out the rough edges of colds, skin problems, or sluggish minds. In this search for better health, Zinc Lactate often pops up as a choice—advertised for its digestibility and the way it's gentle in the gut compared to some other forms of zinc. Still, getting the dose right sounds simpler than it actually feels.

Numbers get tossed around pretty freely: you’ll hear 8 mg for women, 11 mg for men as daily dietary zinc intake from reputable groups like the National Institutes of Health. These amounts aren't pulled from thin air. They're what most healthy adults should draw from food and supplements together for normal enzyme function and cell repair. Zinc Lactate supplements supply elemental zinc—the part your body uses—not the total weight on the bottle.

Here’s the catch: the actual zinc in Zinc Lactate is only a fraction of the compound's total mass. For example, a pill with 50 mg Zinc Lactate may only offer 10–15 mg elemental zinc. It pays to read labels carefully and convert those numbers with a calculator if you want to stay in the healthy range.

Some folks think, “If a little helps, more should help more.” That’s not how minerals like zinc work. If you’re taking over 40 mg daily (the tolerable upper limit set by health authorities), you start running into trouble: copper deficiency, weakened immunity, stomach cramps, and a permanently upset gut. The body treats excess zinc almost like a stubborn guest who won’t leave the party. It blocks out other helpful minerals and upsets the normal checks and balances inside the gut.

I’ve seen people trying “megadose” routines chasing memory boosts or hoping to zap every virus in sight. It doesn’t end well. Nausea, metallic taste, and, over time, real health backslides become hard to ignore.

Digestive complaints, existing medications, age, pregnancy, and diet change best doses. Vegetarians might get less zinc from food, since plant-based zinc is harder to absorb. Older adults sometimes absorb less zinc and need a little more. But going off-rail with high-dose supplements isn’t smart without actual bloodwork or a doctor in the loop.

Zinc works best with a steady diet: meat, shellfish, dairy, beans, whole grains. Supplements like Zinc Lactate fill in the gaps only when there’s a real need, like a diagnosed deficiency, after checking with a professional.

Safe supplement routines usually land between 10 and 20 mg elemental zinc per day—taken with food, not on an empty stomach. This approach stops bother to the gut and helps with absorption. People often forget to factor in how much zinc slips in from multivitamins, fortified foods, and over-the-counter cold medications as well.

Overshooting with several products or piling supplements on top of a zinc-rich diet leaves you swimming in confusion or, worse, real health risks. A clean solution starts with tallying up daily totals—food and pills together—aiming for the recommended dietary amount, not more, steering clear of the side effects that spoil all the good zinc can offer.

Zinc gets a lot of hype for its immune-boosting power and its spot in the vitamin aisle. In the supplement world, zinc lactate often lands on ingredient lists thanks to its solid solubility and easy absorption. Many folks swallow these pills or chew them in lozenges, picturing glowing health. It feels simple — take a tablet, stay healthy. But bodies don’t always go right along. Side effects sometimes creep in, and these are worth talking about, especially if you’ve ever dealt with surprises from a new supplement.

If you’ve ever tried zinc lactate on an empty stomach, you might remember a wave of nausea not long after. Zinc in any form presses its luck with digestion; this salt version can turn a calm belly into a churning mess. Nausea, stomach cramps, or even a sudden dash to the bathroom show up for many. Some people ignore these cues and keep going, thinking the stomach just needs to toughen up. I learned the hard way just tossing back a zinc tablet with coffee isn’t a shortcut to wellness — it’s a shortcut to feeling queasy all morning.

Zinc supplements can play a trick on the tongue. Some folks notice food tastes “off” after regular zinc use. Meals lose their punch, coffee seems dull, and things just feel bland. Doctors recognize this as a real side effect: zinc can mess with taste and smell at higher doses. Losing pleasure in food adds up to a quality-of-life hit, not just a minor inconvenience. For some, cutting the supplement clears it up, but taste can take a while to bounce back.

Plenty of people imagine that “natural” or “essential” means risk-free. That isn’t true with zinc. Zinc overdoses stack up over days, especially if you ignore the recommended dose on the label. High zinc levels start to crowd out copper in the body, setting off nerve and immune issues. People chasing immunity sometimes dose far above what’s advised, and then start running into weird symptoms: fatigue, unexplained fevers, tingling in fingers, and immune bugs that just won’t clear up. FDA guidelines recommend no more than 40 mg of elemental zinc daily from all sources, unless a doctor says otherwise.

Allergies to zinc lactate don’t happen often. When they do, the reaction usually shows up fast — swelling, itchiness, hives, or trouble breathing. I haven’t seen this myself, but clinics warn to watch for these signs, as supplements can trigger full-blown allergy even if zinc itself is an essential mineral. Zinc can also mess with some medications, lowering the effectiveness of antibiotics or interfering with diuretics, so it always makes sense to run changes past a healthcare provider.

Popping pills won’t fix poor nutrition. A balanced diet does most of the work, and the richest zinc sources come from meat, beans, seeds, and nuts. For most people, supplements only make sense in real deficiency — something doctors can help sort out. If supplements seem like the answer, splitting the dose, taking with food, and sticking to the label makes stomach trouble less likely. Staying honest about your other medications also helps keep side effects in check. Nobody wants their immunity adventure to turn into a stomach upset or a flavorless month of meals.

Most folks assume something with “zinc” in the name just means a mineral, and minerals don’t raise many ethical red flags. But throw “lactate” into the mix and the conversation changes. Lactate hints at a link to “lactose,” the sugar found in milk, so people who avoid animal products start asking questions. For both vegetarians and vegans, ingredient origins go beyond simple lists. If you’re watching what you eat for personal, ethical, or health reasons, you learn pretty quickly to ask who made it, where it came from, and how it was processed.

Zinc lactate is a compound made from zinc and lactic acid. Most lactic acid today comes from fermenting plant sugars, like corn or beets. Producers use bacteria to turn these sugars into lactic acid in a process pretty far removed from cows or dairy. The zinc part comes from mined minerals, not from living things. So on paper, the raw ingredients line up just fine for vegetarians, and most vegans see no red flags either.

In my own grocery aisle experiences, vegan shoppers (me included) look for clarity, not assumptions. Plenty of supplements use animal-based binders, capsule shells, or even processing agents that dodge the ingredient label. Lactic acid makes people think of milk, but plant ferments can handle production without touching a dairy cow. The one snag can be in the little details: sometimes, a niche producer uses animal byproducts or gelatin in the manufacturing process, even if they don’t show up as ingredients in the finished product.

Nutrition supplement companies don’t always make it easy for consumers. The right thing is for brands to declare exactly how their zinc lactate gets made. A lot of packaging only says “suitable for vegetarians” or “vegan-friendly” if the company has paid for certification. Smaller brands slip under the radar or don’t want to pay the premium for that badge. So the best route often involves asking questions, digging into manufacturer websites, or sending off an email.

Some people trust guidance from big certifying groups, like The Vegan Society. If a product displays this kind of stamp, I breathe easier. Still, the extra level of caution comes from seeing how a company handles cross-contamination or if they’re running mixed production facilities. One company may use pure plant sources for lactate, another sources lactic acid in a factory that processes animal products on Tuesdays. Until regulations get tighter and supply chains become more transparent, every vegan or vegetarian still plays detective.

Clear, honest labeling helps everyone. If laws set stricter standards around ingredient sourcing and companies had to describe those origins, shoppers could make choices with confidence. I’ve noticed consumers push hard for better labeling, pressuring brands to define what “vegan” means. There’s a place for third-party oversight, and for brands to show off diligence. Firms selling to plant-based markets would win trust by sharing sourcing practices up front.

Zinc lactate works for most vegetarians and vegans when made from plant fermentation. With so much riding on a simple statement of origin, the supplement industry should make its supply chain as public as its nutrition panels. Until then, most of us will keep reading the fine print, reaching for the customer service phone number, and taking nothing for granted.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | zinc bis(2-hydroxypropanoate) |

| Other names |

Zinc dilactate Zinc(II) lactate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈzɪŋk ˈlæk.teɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 16039-53-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1207933 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9159 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3305497 |

| ChemSpider | 12426 |

| DrugBank | DB14504 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.227.324 |

| EC Number | 231-793-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 113732 |

| KEGG | C01452 |

| MeSH | D015928 |

| PubChem CID | 24876952 |

| RTECS number | OW7600000 |

| UNII | 7KID0QI09I |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H10O6Zn |

| Molar mass | 243.50 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | D=2.8 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -2.6 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.14 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.60 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 3.52 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 219.3 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1548.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CB05 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H319 |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid breathing dust. Wear protective gloves, protective clothing, eye protection, and face protection. Wash hands thoroughly after handling. Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat: 2,950 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) Oral - rat: 2970 mg/kg |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 10-30 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Calcium lactate Magnesium lactate Zinc gluconate Zinc sulfate Zinc acetate |